“Gods, celestial beings, humans, beasts, and birds:

from him in diverse ways they spring;

In-breath and out-breath, barley and rice,

penance, faith, and truth,

the chaste life and the rules of rites:

from him do they spring.” (Mundaka Upanishad, 2.1.7)

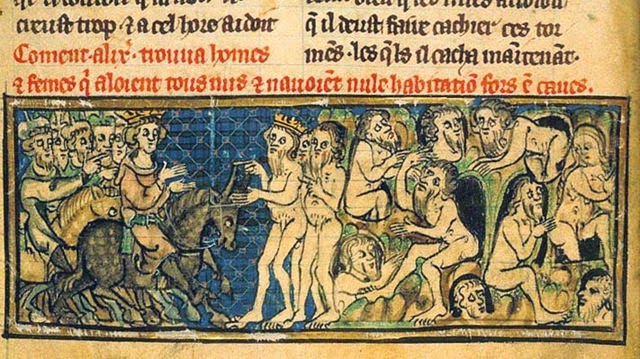

Sources tell us that Alexander the Great met the naked men outside Taxila. The city was a meeting-place, a place where three trade routes met in the heart of the Punjab, “a true caravan city,” as the historian Richard Stoneman puts it. (Stoneman 53) Two miles outside the city walls, upon approaching a grove of trees, the Macedonians were surprised to see a group of ascetics practicing yoga poses in the nude. Alexander sent one of his officers to speak to the men.

After an initial rebuff – go away, please, this is our naked yoga hour – the sages agreed to an audience. They “laughed at the Greeks’ cloaks and knee-high boots and told them to undress if they wanted to talk,” writes the historian William Dalrymple. (Dalrymple 33) This wasn’t a condition Alexander was willing to meet, so he did the next best thing: he invited the men – dubbed the “gymnosophists” by his retinue, the “naked wise men” – to dinner.

During the meal, the Greeks were intrigued by their guests’ vegetarianism and their commitment to avoiding all physical pleasures through strict self-discipline – instead of sitting or reclining to take their meals, the gymnosophists ate while standing on one leg. They peppered the Greeks with questions about Diogenes, Socrates, and Pythagoras. They explained that the way to avoid suffering was by renouncing passions and controlling desires. (Dalrymple 33-34)

Alexander, in his turn, asked them his own questions. “Who are more numerous, the living or the dead? Which is stronger, death or life? Which side is better, the left or the right?” (Stoneman 298) No offense to the conqueror, but these are the kinds of questions an old weightlifting coach of mine used to ask: “would you rather be itchy or sticky?” You’d think Aristotle’s most famous pupil could do better.

The gymnosophists fired back: “Since you are a mortal, why do you make so many wars? When you have seized everything, where will you take it?” (Stoneman 299)

Alexander had swept through the Persian empire like a flame through dry brush. On his advance into northwestern India (modern Pakistan and Afghanistan today), he’d encountered a dazzling array of strange religious practices along with the monsoons and the cavalry units mounted on elephants. But few seem to have affected him quite as much as the gymnosophists and their pointed questions.

Just a few short years later, when he died, Alexander was laid out on his funeral bier with one hand left outside the winding sheet. This was in accordance with his instructions: he wished to show the world that everyone, even a warrior-king leaves the world empty-handed.

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time.

Books of All Time is a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode 18: The Upanishads, Part 2: Dionysus, Son of Indus. As always, if you want to read the transcript of this episode or see the references I used to write it, you can visit our website, www.booksofalltime.co.uk. There’s a link in the show notes if you need it. Let’s begin.

This week, we’re following up our episode summarizing the Upanishads with a closer look at similarities and connections between Ancient India and Ancient Greece at the time the Upanishads were being composed and compiled. I’m going to take you through some of what I’ve read so far about Ancient Greece and Ancient India’s interactions. We’ll look at how they may have interacted long before Alexander the Great’s time, and then we’ll walk through some of the similarities in their mythologies, early spiritual practices, and their philosophical ideas.

We’re going to be spending quite a lot of time with these two cultures next year, and I think it’s worth taking some time here to compare them – they have a lot more in common than many of us in the West have been led to believe, and they may have interacted much more than we believe, too.

As the historian William Dalrymple puts it in his new book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, “India was not some self-contained island of Indianness, but . . . a cosmopolitan and surprisingly urban society full of traders from all over the world.” (Dalrymple 31) Alexander the Great’s naked dinner guests were far from the first Indians to sit down and break bread with Greeks.

We need to define when and where we’re talking about. For the “when”, we’re looking at the large window during which the major Upanishads were written – approximately 800 BCE to 300 BCE. That’s a big window spanning many different iterations of both “Ancient India” and “Ancient Greece,” especially given how in flux this entire region was at the time.

As the scholar George P. Conger put it, “it is as if a great cultural wave or groundswell swept across Asia, demanding that the childish polytheisms give way to something more advanced.” (Conger 128) I don’t know if the polytheisms were childish, exactly – Conger was writing in 1952, which explains the chauvinism, I guess – but they were certainly giving way.

On the Greek side, you’re going from the composition of the Homeric Epics and Hesiod (and the polytheism they described) toward the teachings of philosophers like Plato and Alexander the Great’s tutor Aristotle. On the Indian side, you’re going from religious practices that revolve around animal sacrifices toward the deep metaphysical ideas present in the Upanishads – ideas which fed into the emerging religions of Buddhism and Jainism.

For the “where,” we aren’t looking at all of modern Greece and all of modern India. To quote George Conger again, “in this connection ‘India’ means less and ‘Greece’ means more than modern usage indicates.” (Conger 103) When I talk about “India” in this episode, I mainly mean the northwestern part of the subcontinent, including chunks of modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. Greece refers not just to the current borders of Greece and its islands, but also parts of modern Italy, Egypt, and other areas of Asia Minor. This expansive definition of “Greece” especially applies once Alexander is on the scene.

So, how did Greece and India interact prior to Alexander the Great? What was happening during the, say, five centuries before he turned up, hopped on his horse Bucephalus, and shocked the world? The most obvious avenue for communication is trade. Merchant sailors from Greece and northwestern India regularly plied the Arabian Seas, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea, and caravans made the trek overland. (Conger 106-107)

Trade between east and west has always happened. William Dalrymple’s book The Golden Road is actually named for the trading routes of the Arabian and Red Sea. “There is evidence,” he says in chapter two of that book, “of pioneering Indian merchants making remarkable prehistoric trading voyages as early as the seventh millennium BCE, when Afghan lapis first turns up in beads found in northern Syria.” That’s nine thousand years ago.

There is plenty of evidence for ongoing communication between India and lands to the west for trade purposes. George Conger notes that Ashurbanipal is on record as trading with India in the 800s BCE – yes, that Ashurbanipal, the one whose library, containing the Epic of Gilgamesh, was dug up by Hormuzd Rassam way back in episode two. Ashurbanipal asked for a “wool-bearing tree,” or cotton plant. He was not the only Mesopotamian monarch to have a taste for Indian goods – excavations of later buildings around Babylon have yielded up Indian teakwood, Indian gems, and Indian rice. (Conger 106-107)

“We may always doubt if highly developed theories about the world are accurately transmitted by untrained men along the trade routes,” Conger goes on, “but stories, legends, and myths pass current everywhere . . . garbled ideas and rudimentary suggestions easily slip through to find lodgment in minds capable of developing them.” (106)

The Greeks were similarly on the go – you may recall that Hesiod’s father was a merchant sailor, and how his success became the source of the inheritance Hesiod disputed with his brother. Hesiod Sr. wasn’t a one-off: John Boardman, in The Greeks in Asia notes that Greek pottery is found in Syria and Mesopotamia as early as the 9th century BCE. (Boardman Loc. 253) “The ancient world was a relatively small place,” Boardman notes. (Loc. 76)

It is true that trading with another nation can connect them to you, creating bonds of friendship. So too can being conquered by the same dude – this creates bonds of trauma. That’s what happened to eastern Greece and Northwestern India during the reign of Darius the Great, King of Persia. Darius (lived 550 BCE to 486 BCE) was a member of the Achaemenid dynasty, kings who had amassed an enormous amount of territory, to which he added yet more land.

I found a sort of league table of ancient empires on Wikipedia, and if that’s accurate, the Achaemenid empire under Darius swelled to 5.5 million square kilometers of territory – bigger than anything the world at that point had yet seen, bigger than the Roman empire at its peak, even (whisper it) ever so slightly bigger than the empire Alexander the Great would control. The Macedonian only managed 5.2 million square kilometers, but then, he only lived half as long as Darius did.

Anyway. The western limit of Darius’s empire was in Macedonia, on the western edge of Greece (he tried, but never managed, to conquer the Greek heartlands, famously getting whooped at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE). The eastern limit was in the Indus valley, and great swathes of north Africa, Egypt, and Mesopotamia lay between the two edges.

The Achaemenid empire was thus poised, says George P. Conger, “to be a long, high bridge between East and West.” (124) Connected by the sword, Greeks and Indians met at the Persian court – they may even have served in its armies together. Where there are meetings, there are exchanges of ideas. Conger supposes it’s possible that Greek medical ideas and texts made their way to India through the Persian court, for example, but we don’t quite have proof of that.

However, one thing we do know is that when Darius wanted someone to explore the Indus Valley for him, he chose a Greek called Scylax. Scylax went down the Indus River around 515 BCE on behalf of his imperial master. He kept a travelogue of his journey which was published and read by his contemporaries, although it’s lost to us. The Greek writer Herodotus (father of history, future Books of All Time episode subject, stick a pin in him, metaphorically, until next summer) had it. He says:

“As to Asia, Darius discovered most of it. There is a river Indos, which of all rivers comes second in producing crocodiles. Darius, desiring to know where this Indos Issues into the sea, sent ships manned by Scylax . . . [who] sailed down the river towards the east and the sunrise till they came to the sea.” (Herodotus, quoted in Stoneman 25)

Isn’t it impressive how Darius discovered most of Asia? Sarcasm aside, it seems that Scylax was able to get back to Darius in one piece – he came out the Indus into the Arabian Sea, and wound up coming ashore somewhere in north Africa. In addition to sharing details about plants, animals, and the basic geography of India, Scylax also made a bunch of stuff up. Dog-faced people, one-eyed people, people who would wrap their enormous ears around them when they wanted to go to sleep. (Stoneman 25) It’s also possible that Scylax is the source of a story about a species of ant particular to India that digs for gold in the ground.

To the earliest Greek writers – those who’d been to India and those who hadn’t – India was a place of wonderful fertility: rich in spices, textiles and precious metals, inhabited by wise and just people (the ones with typically sized ears, anyhow). But it was also simultaneously a place of savage danger – a den of tigers. Scylax’s reports about India as handed down through subsequent generations of interpreters created the mold of a stereotype that would be difficult to break.

[music]

Now on to the mythology. It’s possible that apparent similarities in the myths and legends of India and Greece have to do with their common heritage. In our episodes on the Rig Veda, I talked about how Sanskrit, the language in which the Rig Veda and the Upanishads were written, is an Indo-European language. That is, it stems from a much earlier language that is also a common ancestor of Greek. A quick aside: it looks as if the Greeks and their contemporaries in the Indus Valley – the descendants of the Vedic people – may also have drawn their writing systems from a similar root, too.

Remember the Bronze Age Collapse, the tumultuous period about 700 years before the time of the Upanishads (and Homer, and Hesiod) when all the civilizations around the Mediterranean experienced some kind of catastrophe? Remember how the Mycenaean Greeks actually lost the habit of writing things down for a couple of centuries? When they started again, they adapted the newfangled alphabetic writing system used by the Phoenicians, a seafaring people they interacted with regularly.

It turns out that the people of northwestern India may have done this as well. The “Brahmi script,” the writing system used to compose and compile the Rig Veda and the Upanishads, shows signs of being influenced by the Phoenician alphabet, or possibly its descendant script, Aramaic. There are some scholars who think this may not be the case, that it’s possible that the Brahmi script arose indigenously, but for now the weight of evidence is on the side of a descent from the Phoenician writing.

To resume with the myths. Back in episode 7, I shared with you the fact that within the Rig Veda, the god mentioned more than any other is Indra. He’s a sky-god, a warrior-god. His origin story, you may recall, shares much in common with the story of Zeus as shared with us by Hesiod in Theogony.

There’s a ravenous father-god – Varuna for Indra; Kronos for Zeus – who devours his children as soon as they’re born to prevent them supplanting him. The mother-goddess deceives her husband, saving her youngest son by getting Bad Dad to swallow a rock. She arranges to have the boy raised in secret. The son grows up to overthrow the tyrannical father and becomes the pre-eminent god, further demonstrating his prowess by destroying a terrible serpentine monster with his weapon of choice: a thunderbolt.

There are also some key differences with the two versions of the story, however: for example, Indra’s wife, Shachi, is not his sister. The same cannot be said of Zeus and Hera.

Other aspects of Greek myth connect with Indian myths, too. In a 2002 address to the Indian History Congress, Professor Udai Prakash Arora states that, “the Vedic Varuna is comparable to Ouranos, Usas is Greek Eos; Sarameya is Hermes; Yavistha is Hephaestus and Swaha may represent Hestia.” (Arora 30)

I looked these up and it’s difficult to find sources that aren’t Wikipedia or hobbyist websites (not to knock hobbyists – I am one, after all). But here goes:

Varuna, god of the sky, was connected in the 19th century with Ouranos by a French philologist called Georges Dumezil. Subsequent philologists have thrown doubt on Dumezil’s working-out of that connection, but both gods are sky-gods with problematic parenting styles. Varuna, to my knowledge, does not suffer the indignity of having his genitals sliced off, though.

Usas, or Usha, is the Vedic goddess of the dawn. She is the sister of Nisha, night. Her Greek counterpart is Eos, also a dawn-goddess, who is the sister of the moon and the sun.

Sarameya or Sarama is a goddess, sometimes depicted as a swift-running hound who serves Indra when he hunts. It was Max Müller, working in the 1850s, who connected her to Hermes, the Greek messenger-god. While Müller’s historical importance to the field is undeniable, he did have a strong fanciful streak. People were picking apart this association as early as 1870. (Cox 1870, p. 452)

Yavistha and Hephaestus are more closely linked. Yavistha appears to be an alternate name for the god Tvashtr, who like his Greek counterpart Hephaestus is a god of fire, metalwork, and crafts. He is the god who forged Indra’s thunderbolt. One striking difference between Tvashtr and Hephaestus is that Tvashtr is not depicted as maimed, deformed, or otherwise ugly – Hephaestus usually is.

Swaha, or Svaha, is the wife of the fire-god, Agni. In some Hindu traditions she presides over burnt sacrifices. If you’re squinting, you can see how this connects her to Hestia – both women who hang around fires – but Hestia is a virgin goddess whose role it is to tend the hearth. I couldn’t find a trace-back for this connection – no philologist or Sanskrit scholar giving his or her opinion on the origins of that link. So take that for what it’s worth.

There are two other Greek mythological figures who have a connection to India: Heracles and Dionysus. In The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks, author Richard Stoneman shows how these connections were likely back-formed by Alexander the Great and/or his contemporary, the writer Megasthenes, who may have accompanied Alexander during his expedition. Certainly Megasthenes wrote about Alexander in his lost book Indica, of which we only have passages and fragments quoted by other writers.

According to Stoneman, the Macedonian Greeks “worshipped a relatively limited range of gods compared with the full Greek pantheon.” (Stoneman 81) One key figure they revered was Heracles, the mythological strongman who was granted immortality by the Gods for his heroics. The Macedonian royal house claimed descent from Heracles. His iconography – often a man dressed in a lion skin, carrying a club – figured heavily in their coinage and art, and Alexander performed sacrifices to him regularly.

There are many stories about Heracles’s feats of strength and endurance. But one of them is actually about a failure of his: at some point in his career, Heracles tried to invade India and failed. Alexander the Great had several motivations for trying to conquer as much of India as possible – clawing back every last inch of Persian territory to revenge himself on Darius III was key among them. One driver, however, seems to have been his desire to emulate his legendary ancestor.

In the Punjab, Alexander and his forces crossed paths with a group of people called the Sibi, who carried clubs and dressed in skins. “The Greeks took them for the remnants of Heracles’s invading army,” Stoneman says. He adds that the club was also an attribute of the Vedic god Krishna – this, along with Krishna’s similar reputation for immense strength and knack for killing otherwise invincible monsters, may have caused Heracles and Krishna to be linked in the minds of later writers. (Stoneman 86)

Dionysus was also important to the Macedonians. He is the Greek god of wine, ecstasy, and divine madness. According to legend, he was born to the mortal woman Semele at a place called Nysa. Now, Greeks had long held that Nysa was somewhere in Arabia – Dionysus has always been read as “a bit foreign” to the Greeks – but its exact location had never been found. Imagine Alexander’s surprise when he came to a place called Nysa high in the mountains near modern Jalalabad, in what’s now Afghanistan. There were vines and ivy growing there – clear tokens, to Alexander’s mind, of the god’s influence on the area. (Stoneman 93)

The people of this “Indian” (scare quotes around that; it was Indian to the Greeks) Nysa also acted like Dionysian revelers: they danced and sang and banged drums in procession. Alexander must have made clear his expectation of seeing or encountering Dionysus, because the locals seem to have got wind of it and played up to him, telling him that in their tradition, Dionysus was the son of the Indus river.

It probably helped that many festivals and rituals indigenous to India resembled Greek celebrations of Dionysus – festivals such as Holi, for example, or celebrations of Kama, the Vedic god of love and pleasure. When it came to Dionysus in India, the Greeks were seeing what they wanted to see. (Stoneman 94)

Modern scholars often associate Dionysus with the Hindu god Shiva. While there are parallels to be drawn between the two, Stoneman notes that Shiva isn’t mentioned in the Vedas and probably didn’t exist in anything like his later form when Alexander the Great was marching through the Indus Valley. If you were going to connect the dots between Dionysus and a god from the Vedic or Hindu pantheons, it would be Shiva’s precursor Rudra. Rudra, like Dionysus, uses intoxicants (soma instead of wine), can be alternately merry or frightening, lives in the mountains, and is often associated with the symbol of the bull. (Stoneman 94-96)

If Dionysus and Heracles came out of India or the Vedic culture, they left little trace. However, they certainly arrived there with Alexander – Stoneman reports that both gods were widely worshipped in the Hellenized regions of India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan for centuries after Alexander’s death. (Stoneman 98)

[Music]

Now we get to the sticky bit: philosophy. The idea of a “philosopher” that we have in the West is largely a Greek one – it’s a Greek term, meaning “lover of wisdom,” though it may not have been coined until relatively recently. For the ancient Greeks, philosophy was the practice of thinking systematically and critically about questions and problems, like: why do we exist? What does it mean to actually know something? What is the mind and why does it wake you up at 3:15 a.m. to pester you about that cruel thing you said to your cousin that one time?

As with the comparative mythology we’ve just looked at, there are interesting parallels between the Greek and Indian schools of thought during the latter half of the first millennium BCE. Beginning with the very earliest Greek philosophers, we can see threads of similar ideas that connect the two cultures’ schools of thought. Whether those threads originated in India or not is difficult to say – we don’t really have the hard, written evidence for that. The similarities, though, are very intriguing, and scholars for centuries have been trying to pull those threads.

In The Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece and Ancient India, Richard Seaford takes a fine-toothed comb to Indian and Greek philosophy, teasing out the most striking parallels between them and trying to explain how they might have come into being. I’ll talk mostly about the parallels he identifies. There are three.

First is monism – the idea that everything in creation is one unified thing. In some cases this unified thing is personified (like Purusa, the cosmic person who is dismembered to create the world in both the Rig Veda and the Briharadanakya Upanishad; in other cases it’s impersonal. Sometimes the individual forms and entities we perceive are manifestations of this one thing; other times they’re illusions. Regardless, everything is unified.

Second is the concept of an eternal, incorporeal inner self, usually cast as a manifestation of the unity, which we must work to know if we are going to know anything about the world or feel at peace in ourselves.

The final common thread is the idea of reincarnation after death – usually reincarnation in which our new body is determined by how ethically we behaved in the life we have just left, but sometimes just random reincarnation.

“Greek metaphysical ideas,” says Seaford, “are much closer to those found in India than to any found in the vast area . . . between Greece and India.” (p. 246) Now. His personal theory is that these similarities in metaphysics exist because (or at least partly because) these two societies happened to be the ones that were adopting money-based economies at the time. That is, he draws a link between the idea of money and the idea of an all-pervading oneness, or something – I am not quite sure I was picking up what he was putting down. However, the multiple reviews of this book that I read by people with actual expertise in philosophy makes me think, you know, maybe I’m not alone in that. (Johnson 2021 p. 2)

Leave the “why” to one side. Where I found Seaford most useful was his historical comparisons. I’m going to walk through three philosophers who came before Socrates and Plato philosophers and pull out ideas they had that line up with ideas expressed in the Upanishads. This will also help us dip our collective toes in the waters of Greek philosophy – we’ll be wading in up to our necks next year, and I don’t know about you, but I’ve forgotten how to navigate those waters. My last college course in philosophy took place during Bill Clinton’s second term in office.

Let us begin with Pythagoras. That’s right: the original Triangle Man. Pythagoras of Samos was probably a real person, and he possibly lived between 570 and 450 BCE, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. He never wrote a word. Everything we know about him came from other people – most famously Plato, who lived 150 years after Pythagoras had died. He seems to have been important in mathematics and music theory as well as in metaphysics.

The metaphysics was what made a cult spring up around him (that, and the stories about his golden thigh, which allowed him to be in two places at once – please, just go to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and read the entry on this guy; I cannot recommend it enough). According to Pythagoras – or at least, according to the millennia-long game of telephone that has passed Pythagoras on to us – the soul is immortal, and it goes through a series of reincarnations after death. The best way to ensure these reincarnations went well for you was through a strict lifestyle with specific dietary rules (no beans – Pythagoras was very firm on this) and religious rituals to follow.

If none of this sounds familiar, I encourage you to go back and listen to last week’s episode. The principal Upanishads are thickly strewn with ideas about the cycle of rebirth and the need to renounce material and worldly pleasures. Recall the Mundaka Upanishad:

“Deeming sacrifices and gifts as the best,

the imbeciles know nothing better.

When they have enjoyed their good work,

atop the firmament,

They return again to this abject world.

But those in the wilderness, calm and wise,

who live a life of penance and faith,

as they beg their food;

Through the sun’s door they go, spotless,

to where that immortal Person is,

that immutable self.” (Olivelle 270)

Seaford emphasizes that this edict of renunciation, this urge toward asceticism, seems to be new to both India and Greece in the middle of the first century BCE. He walks exhaustively through the Rig Veda, Homer, and Hesiod looking for signs of it. He concludes “nowhere can we find the tiniest suspicion of a wish to renounce the material world in favor of some spiritual quest.” (p. 62)

Next up was Heraclitus, who was active around 500 BCE. He lived in the city of Ephesus, which was controlled by the Persians during his lifetime. Persian metaphysics focused on fire as a primary force in the world, and Heraclitus also promoted fire as his preferred candidate for the underlying substance of reality – debating what reality was “made of” was a hot topic among 6th-century BCE philosophers. He’s also well-known for articulating the idea that everything is in a constant state of flux: the world never just is, it’s perpetually becoming. Some believe him to be the source of the saying that “no man ever steps in the same river twice.”

Heraclitus also ascribed the structure of reality to a unifying force called logos. It’s tricky to define – George P. Conger’s essay “Did India Influence Early Greek Philosophers?” runs through about seven different possible interpretations (Conger 118-119), but the general sense seems to be that he meant a unifying wisdom or reason, rather like the concept of brahman.

You remember brahman, right? The all-pervading consciousness behind all things, of which your atman is just one emanation? It’s also frequently described as a reasoning force. Here’s a passage from the Briharadanakya Upanishad to explain it:

“In the beginning this world was only brahman, and it knew only itself, thinking, ‘I am brahman.” As a result, it became the whole.” (Olivelle 15).

Then we have Parmenides. Dates, as always, are uncertain, but he seems to have been born around 540 BCE, and he was an Ionian Greek who lived on Samos, off the coast of modern-day Turkey. Parmenides was the author a long philosophical poem, On Nature. We don’t have the poem itself anymore: we just have long passages of it quoted by other philosophers. Socrates (as written by Plato) was fulsome in his praise of Parmenides: he calls him “the great leader . . . venerable and awful.” (Domanski 47)

In On Nature, Parmenides lays out a metaphysical view of the universe as unified, with all forms flowing from a single source. So far, so brahman. He also asserted that you can’t understand the true nature of reality via the senses – instead, you have to use your inner reasoning and contemplative faculties to approach it. So far, so atman.

Interestingly, he begins this poem with a long metaphorical passage describing the soul – the inner source of reason – as a chariot. The Katha Upanishad – you remember, it’s the one where the boy Nachiketas goes to visit Yama, the god of death, and has a long philosophical chat with him – also takes this approach.

While we have no direct evidence of a connection between the two, the Katha Upanishad very likely was circulating within Parmenides’s lifetime. Now, it’s entirely possible that in a time when you had multiple cultures who fought and travelled using chariots, that this sort of imagery could have arisen independently, but the parallels are really striking when you look at them up close, as Andrew Domanski, a scholar from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, did in a 2006 article.

Let’s look at the Kantha Upanishad first. Yama, the god of death, is explaining to Nachiketas the nature of the atman.

“Know the self as a chariot,

and the body, as simply the chariot.

Know the intellect as the charioteer,

and the mind, as simply the reins . . .

When a man lacks understanding,

and his mind is never controlled;

His senses do not obey him,

as bad horses, a charioteer.

But when a man has understanding,

and his mind is ever controlled;

His senses do obey him,

as good horses, a charioteer.” (Olivelle 238-239)

Death then links being able to control your personal atman-chariot as the path toward escaping the cycle of death and rebirth.

In Parmenides (or at least in other people’s quotes of Parmenides), we get this:

The steeds that carry me took me as far as my heart could desire,

When once they had brought me and set me on the renowned way

Of the Goddess, who leads the man who knows through every town.

On that way was I conveyed; for on it did the wise steeds convey me,

Drawing my chariot, and maidens led the way.

And the axle blazing in the socket-

For it was urged round by well-turned wheels at each end –

Was making the holes in the naves sing, while the daughters of the Sun,

Hasting to convey me into the light,

Threw back the veils from off their faces and left the abode of night. (Parmenides, quoted in Domanski 50-51)

This seems superficially like the Kantha Upanishad at first – it’s a lot more flowery and, well, Greek than the Vedic verse is. The chariot is very concrete and real: he talks about the axles and the wheels and whatnot. But then he arrives at a house, “the abode of day and night,” and is greeted by the goddess of justice:

“And the Goddess greeted me kindly, and took

My right hand in hers and spake to me these words:

‘Welcome, O youth, that comest to my abode

On the car that bears thee, tended by immortal charioteers.

It is no ill chance, but Right and Justice, that has sent thee forth to travel

On this way. Far indeed does it lie from the beaten track of men.

Meet it is that thou shouldst learn all things,

As well the unshaken heart of well-rounded truth,

As the opinions of mortals in which is no true belief at all.

Yet nonetheless shalt thou learn these things also – how the things that seem,

As they pass through everything, must gain the semblance of being.” (Domanski 50-51)

That last line is the kicker: “how the things that seem, as they pass through everything, must gain the semblance of being.” He is here to learn about the fundamental truth, of which all reality is just an emanation. Other people’s opinions cannot lead you to that truth, you have to ride in the chariot to a place outside of strife and sensation until you reach an understanding of the unity of creation.

Domanski argues that Parmenides is not conducting an act of cold logical calculation in expressing his philosophy – he says it is describing, “in vivid and concrete terms, man’s spiritual journey from darkness to light, from ignorance to truth.” (Domanski 52)

Parmenides’s writing is, like much of the Upanishads, a kind of intellectualized transcendence – ecstatic wisdom. But it contains the seeds of something bigger. As Richard Seaford puts it: “We feel that with Parmenides reasoning has almost reached the degree of abstraction that will allow it – not long afterwards, with Plato and especially Aristotle – to reflect on itself.” (Seaford 16)

[Music]

So. Can we prove that the myths and ideas presented in the Upanishads had a direct influence on Greek society and culture? Well, no. We don’t have the direct evidence. We can’t prove it, no. But the similarities in mythologies and are striking, and given the strong trade and political links between the two areas, particularly once the Persian empire connected parts of both regions, it’s not out of the question.

After Alexander the Great entered the Indus Valley, however, the connections that were previously implicit became explicit, thanks in no small part to his naked dinner guests from the start of the show. Traveling with Alexander was Pyrrho of Elis (c. 365 – 270 BCE), one of several philosophers who, like Napoleon’s team of scientists in Egypt, were charged with recording observations about the land Alexander thought he was going to conquer. Pyrrho had been a sceptic prior to his arrival in India. After meeting the gymnosophists, he changed. According to William Dalrymple, Pyrrho “adopted a life of wandering and austerity, living in solitude and avoiding what he regarded as the pointless seduction of sensual pleasures.” (Dalrymple 33)

He appears to have become a Buddhist – this may give us a clue about what sect the naked philosophers belonged to. He “embraced a position of agnosticism” (again, per William Dalrymple) and may even have practiced physical yoga postures, holding one pose all day to achieve a tranquil mental state. (Dalrymple 34)

Sources don’t tell us whether he was nude when he did it.

That’s this week’s episode. I hope you’ve enjoyed this slight meander through ancient India’s relationship with Greece (and the rest of the ancient world). One of the things I’ve been learning during this show is just how cosmopolitan and interconnected human society has always been. As a species, we have always sought to explore new places and consider new ideas (and find new markets for our lapis beads and teak). And we’ve sought to explore inward, too – an exploration the Upanishads calls us to consider our highest duty.

Next up, we’ve got a one-off: we’re going back to Greece to hear from the poet who was, until fairly recently, the earliest known woman author. Join me on Thursday, November 7 for “Episode 19: Sappho’s Hymn to Aphrodite – The Tenth Muse.”

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. The Disclaimer Voice of Doom is Ed Brown. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also follow us on social media: we’re on Bluesky, Instagram, Facebook, and also on X, formerly known as Twitter. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Tantor Media, Inc, 2021.

Olivelle, Patrick. Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press, 2008.

“Alexander and the Gymnosophists.” MANAS, southasia.ucla.edu/history-politics/ancient-india/alexander-and-the-gymnosophists/.

Arora, Udai Prakash. “Sectional President’s Address: ‘ANCIENT INDIA AND THE GREEKS.’” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 63, 2002, pp. 29–85, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44158076.

Conger, George P. “Did India Influence Early Greek Philosophies?” Philosophy East and West, vol. 2, no. 2, 1952, pp. 102–128, https://doi.org/10.2307/1397302.

Dalrymple, William. The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World. St Martins Press, 2024.

Domanski, Andrew. The Journey of the Soul in Parmenides and the Kantha Upanishad, University of the Witswatersrand, repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/14526/Domanski_Journey(2006).pdf.

Johnson, Monte Ransome. “The Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece and Ancient India: A Historical Comparison by Richard Seaford (Review).” Philosophy East and West, University of Hawai’i Press, 25 Mar. 2021, muse.jhu.edu/article/786550.

Seaford, Richard. Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece and Ancient India: A Historical Comparison. Cambridge University Press, 2024.

Stoneman, Richard. The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Leave a comment