“O my heart which I had from my mother! O my heart of my different ages! Do not stand up as a witness against me, do not be opposed to me in the tribunal, do not be hostile to me in the presence of the Keeper of the Balance . . . . Go forth to the happy place whereto we speed; do not make my name stink in the presence of the god!” (Faulkner et. al. plate 3)

Eugene Grébaut was certain he had thwarted the smuggler at last. It was 1888, and Grébaut, in his capacity as the Director of the Antiquities Service of Egypt, was attempting to enforce the new laws which gave Egypt the right to stop foreign collectors from taking its ancient treasures out of the country without permission. This particular smuggler was a crafty character, and he had eluded Grébaut all season. The smuggler had reportedly purchased an unusually fine set of funerary papyri from a gang of grave-robbers working around the Valley of the Kings in Thebes.

Grébaut had tried to run the smuggler to ground in Thebes, but he was able to get his prizes onto a boat and head north on the Nile to Luxor, where he had a storehouse. Grébaut had given chase in a steamboat, but nearly lost the trail of his quarry when the steamboat driver took a detour to attend a family wedding. Eventually Grébaut made it to Luxor, where he discovered the smuggler’s storehouse in a building adjoining the Luxor Hotel. He sealed it off. He posted guards from the Antiquities Service around both entrances. The next day, he would make a formal complaint to the smuggler’s consulate and have him arrested and prosecuted.

The smuggler had other plans. He was well-connected, and his employers had given him quite a bit of walking-around money to work with. He arranged for the guards from the Antiquities Service to have a long, boozy dinner at the Luxor Hotel. While they were engrossed in their meal, he also arranged to have a team of men dig into the basement of his storehouse and winkle out everything he was planning to smuggle.

Here’s how the smuggler describes the scene in his self-serving, but very entertaining, 1920 biography, By Nile and Tigris:

“[M]an after man went into the [basement] of the house and brought out, piece by piece and box by box, everything which was of the slightest value commercially . . . In this way we saved the Papyrus of Ani, and all the rest of my acquisitions . . . and all Luxor rejoiced.” (Budge, 1920, quoted in Wilkinson, p. 222-223)

Until his dying day, the smuggler never once expressed the slightest scrap of shame or guilt for his trickery. And why should he? His employers, the Trustees of the British Museum, were delighted with his initiative and with the results. They rewarded him handsomely for his success. His name was Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, and this was his first journey on behalf of the Museum. He would make another 13 trips to “acquire” antiquities over the next 25 years. But this first one gave him a calling card: the Papyrus of Ani remains one of the British Museum’s principal treasures right up to the present. It is one of the most well-preserved and beautifully executed examples of the ancient Egyptian compendium of ritual and mythology, The Book of Going Forth by Day, better known to us as The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time, a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode five: The Egyptian Book of the Dead, Part One – This Thing Reads Like Stereo Instructions. Let’s begin.

As I mentioned in the intro, The Egyptian Book of the Dead wasn’t called the Book of the Dead by the ancient Egyptians. That’s a name given to it in the 1840s by the German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius, who was one of the first to translate a copy of The Book of the Dead in the decades after Jean-Francois Champollion broke the hieroglyphics code. According to the Egyptologist Ogden Goelet of New York University, there’s also a long-standing misconception about The Book of the Dead, which is that it’s a sort of bible of the Egyptian religion – that it’s an authoritative scripture that tells people what to believe and how to behave. (Faulkner et. al. 13) That’s not at all what it is: it’s a manual for dead people.

If you’ve ever seen Tim Burton’s 1988 film “Beetlejuice,” there’s a Handbook for the Recently Deceased that appears throughout the story. It contains tips about what to expect in the afterlife, how to avoid being completely annihilated through exorcism or being eaten by sandworms, how to communicate with the living, etiquette tips, and so on. More than once a character complains about the stilted quality of the prose in this handbook by saying “this thing reads like stereo instructions.”

This is basically the function – and, honestly, the experience of reading – the Egyptian Book of the Dead. It is fascinating for what it tells you about the Egyptians’ mythology and worldview, but it can be hard work. You’re not taking it to the beach with you. It’s a series of spells for the spirit of the dead person to recite as he navigates the underworld and tries to attain eternal life. And it is almost always a he we’re talking about; Egyptologists say it’s rare to find a Book of the Dead in a woman-only burial.

Spells weren’t an occult, secret thing in ancient Egypt. They were a feature of daily life. You’d use spells for all the usual worries – safe childbirth, warding off illness, guarding against thieves, et cetera. You could write your own, or, if you weren’t literate or needed something especially potent, you could arrange to have a priest write you one. While spells were used by Egyptians of every class, the spells in The Book of the Dead have their roots in funeral practices that were originally reserved only for the pharaoh.

The earliest versions of these spells date back to about the time that the Sumerians were first writing down The Epic of Gilgamesh – 2400 BCE. They were painted on the inside of pyramids for the benefit of the spirit of the king, who was destined to take his place among the gods in eternity. The Pyramid Texts, as they are known, depict the king merging with (or becoming identified with) Osiris, the god of the underworld, and refer to him as “the Osiris King’s-Name.”

But later, the spells of the Pyramid Texts began appearing on coffins of members of the lesser nobility who also wanted to partake of the afterlife as gods. Around 1500 BCE, these Coffin Texts began to be written down onto papyrus scrolls as what we’d recognize as The Book of the Dead. Now which anyone wealthy enough to afford mummification could have access to the afterlife as an Osiris – trickle-down apotheosis, I guess.

These papyri were produced more or less continuously for a millennium and a half. According to the sources I’ve looked at, The Book of the Dead peters out in the Ptolemaic dynasty around 50 BCE (the Ptolemies included Cleopatra, who would eventually lose Egypt to the Romans in 33 BCE).

Like our previous works, The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Tale of Sinuhe, The Egyptian Book of the Dead is not the work of one named author. It also doesn’t have a standard, authoritative version. But it does have a standard purpose: the spells within it help the spirit of the dead person navigate the underworld and pass various tests so that they can spend eternity as a god. Lepsius, the Egyptologist from Germany, invented a system for classifying these spells.

As of today, scholars have used his system to identify 192 different spells across all the different known versions of the Book of the Dead. The evidence shows that the spells were changed and added to over time, but they are remarkably consistent. In the extremely helpful book “How to Read the Egyptian Book of the Dead”, author and Egyptologist Barry Kemp notes that of the 192 spells, 113 can be traced back to the original Coffin Texts, which had been created 500 years before the earliest-known Book of the Dead. (Kemp Loc. 128)

Not all these spells appear in the same order, and not all of them are present in each copy—the exact structure of each Book of the Dead seems to have depended on what the dead person could afford. The Papyrus of Ani that Budge found for the British Museum, for instance, clocks in at 78 feet long (24 meters), but others have been found that are much shorter. The wealthiest people could afford to have a bespoke Book of the Dead created for them on fresh papyrus. Others would purchase a ready-made copy from a scribal workshop run by priests. These ready-made copies had blank spaces where artisans could write in the name of the dead person as needed.

Research on the Papyrus of Ani has led scholars to conclude it is one of these off-the-shelf editions, and that it was made sometime around 1250 BCE. This makes sense given Ani’s place in the social hierarchy: he was a royal scribe. He would have been an important and highly skilled civil servant, to be sure, but a servant nevertheless.

In spite of its pre-fab nature, the Papyrus of Ani is prized for how well preserved it is and for the high quality of its illustrations. The text, however, leaves something to be desired. The Egyptologist and former British Museum curator Richard Parkinson, speaking on an episode of BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time in 2017, noted that Ani probably didn’t read through his copy once it was delivered, because there are several places where his name is scrawled in hastily, or even misspelled. (Bragg 2017) You also get several spells that repeat throughout the text, or spells that contradict one another. However, these errors in the text were deemed forgivable if the illustrations were well done. The Egyptians believed that the images and words worked together to give the work its sacred power.

Ogden Goelet, in his commentary for the 1998 Chronicle Books edition of The Egyptian Book of the Dead that I’ll be referring to throughout this show, notes that while there was never a settled text for the Book of the Dead, from about 600 BCE onward it settled down into more or less a standard structure. This roughly breaks down into four parts:

- First, the dead person enters the tomb, where he must recite spells to regain the powers of movement and speech.

- Second, the dead person speaks incantations that give him the right to travel across the sky in the ship of the sun with the god Re (or Ra, but my edition calls him Re, so that’s what I’m sticking with). Then he descends into the Duat, the underworld, where the ship of the sun travels at night.

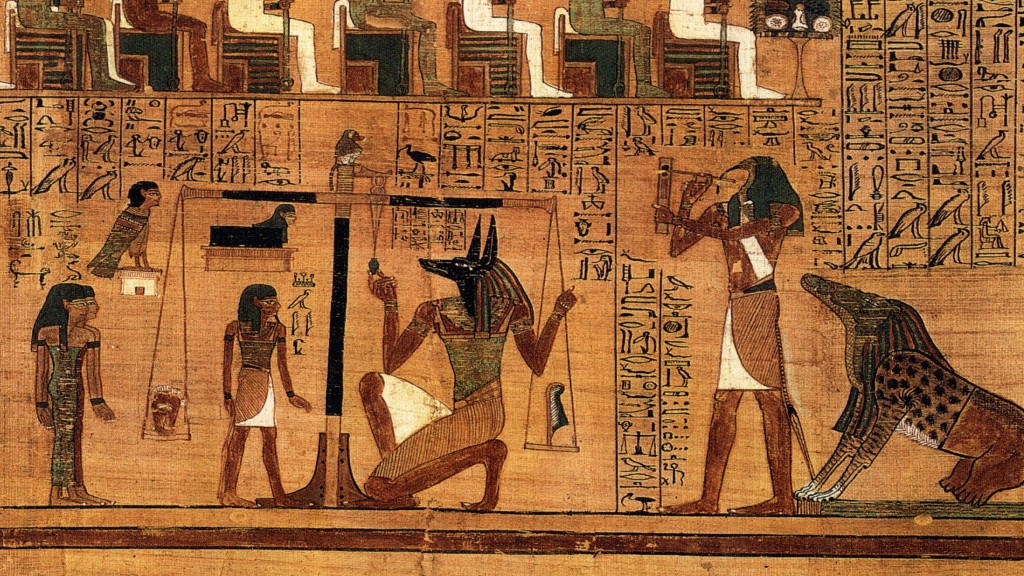

- Next, the dead person must navigate the many perils of the Duat, to gain admission to the palace of Osiris, god of the underworld. There he is judged by a tribunal of 42 minor deities, and has his heart weighed by Thoth, the god of writing, wisdom, and magic.

- Finally, having successfully passed the weighing, the dead person assumes his place in the universe among the gods. (Faulkner et. al. 141)

It’s a little tricky for me, your friendly neighbourhood podcaster, to summarize The Book of the Dead the way I did with Gilgamesh and Sinuhe. But what I can do is walk through this standard structure and look at one or two of the most important spells for each one to give you an idea of what these sounded like, what they talk about, and what they can tell us about the Egyptians and their hopes or anxieties for the afterlife.

So in section one of The Book of the Dead, the spells are generally arranged around protecting the newly mummified body. If you were ever taught about Egyptian mummification at school, you probably have very vivid memories of how the body was prepared – it was ritually washed, then various important organs were removed through a slit in the side of the corpse’s torso to be placed in jars at the foot of the coffin.

The brain, which the ancient Egyptians considered useless – a weird spongy growth that helped the skull keep its shape and nothing more – would be removed via a hook pushed through the nostril. A personal aside: this is why I was never comfortable learning to crochet, no matter how enthusiastically my mother encouraged me. I always imagined that crochet hook going right up my nose and digging out the old electric meatball.

Once the various organs were removed, the body was piled with natron, a naturally occurring soda ash found in deserts that is wonderfully effective at drying out muscle tissue and preventing bacterial growth. Natron took several days to work its magic, and once the body had dried out, the priests in charge of the mummification would wrap the body over and over again in linen strips to imitate the appearance of Osiris, god of the underworld – he is always portrayed in Egyptian art as wrapped in linen with only his head and hands (which are usually colored green) free.

In the process of wrapping the body, the priests would often enclose small objects, such as protective amulets, to further guard the tomb, the body, and the spirit of the dead person. Some of the spells specifically indicate that they are to be said over or carved into amulets and other objects. They would also place The Book of the Dead in the tomb near the dead person’s coffin, the way you might leave a novel on your nightstand.

Once the body is secure, the next step is to slowly revive it, restoring its ability to speak and move the way that it did in life. There are spells that prevent the body from rotting; spells that restore the power of speech and of breath; spells that give the spirit of the dead person the ability to eat or to walk again – honestly, it reminds me of how Dorothy wakes up the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz. And as with the Tin Man, the most important spells are about letting the deceased keep his heart. Here’s part of spell 26:

“My heart is mine in the House of Hearts, my heart is mine in the House of Hearts, my heart is mine, and it is at rest there . . . . My mouth will be given to me that I may speak with it, my legs to walk, and my arms to fell my enemy. . . . I shall be aware in my heart, I shall have power in my arms, I shall have power in my legs, I shall have power to do whatever I desire, my soul and my corpse shall not be restrained at the portals of the West when I go in or out in peace.” (Faulkner et. al. plate 15)

“Fell my enemy”. That’s interesting, no? What could a dead person possibly have to fear in the afterlife? Quite a lot, as it turns out – the landscape of the underworld was fraught with various perils. Failing to navigate them effectively could consign the dead person to complete oblivion.

But we’ll get to those in due time. For now, the dead person is ready to do what the Egyptian title of this work suggests: he is ready to go forth from his tomb into the daylight. Spell 9 describes this process with some references to a few key Egyptian myths:

“I have come that I may see my father Osiris and that I may cut out the heart of Seth who has harmed my father Osiris. I have opened up every path which is in the sky and on earth, for I am the well-beloved son of my father Osiris. I am noble, I am a spirit, I am equipped; O all you gods and all you spirits, prepare a path for me.” (Faulkner et. al. plate 18)

Osiris, as mentioned, was the god of the underworld, but he was also the god of fertility and agriculture—that’s why he’s almost always depicted holding a shepherd’s crook and a flail. Part of his myth was that he was murdered by his brother Seth in a struggle for his throne. Seth dismembered Osiris, leaving his body parts strung along the Nile, where they were found by Osiris’s wife Isis.

Isis managed to impregnate herself using, ahem, a key member of the dismembered body—whether she magically revived him or just used the surviving part in question depends on when or by whom the myth is being told—and the son she conceived, Horus, would eventually avenge his father by battling with Seth. Horus lost an eye, Seth lost his testicles, and Horus became the god of kingship. Horus is one of the two gods with a falcon’s head, by the way – he is the one who’s always wearing a red and white crown on his head.

So by claiming to be Horus in spell 9, the deceased person is claiming kinship with the god Osiris. He’s declaring his intention to show his allegiance to Osiris by magically re-enacting Horus’s defeat of Seth. Note that nowhere in this spell is the deceased required to say he believes any of this—he just has to recite the right words and butter up the right gods to achieve his goals. According to Barry Kemp, “the Egyptians were far less interested in what the gods did than what the gods stood for” (Kemp loc. 388), and they also felt that names and identities were inseparable. As with the fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin, knowing the accurate name of a supernatural being in ancient Egypt gave you power over it. So if you wanted to earn the favor of the god of the underworld, you’d start by claiming the name of a god he loved.

Further spells in this section show just how much favor the dead person gains by claiming the identity of Horus: they give him the power to shift his shape. He can be a falcon, a swallow, a heron, a snake – he can go in and out of his tomb as he pleases. But usually, he will go to the riverbank and start reciting hymns of praise to the sun god Re. Re, if you’re wondering, is the other falcon-headed god, the one who’s always shown with the solar disk above his head.

After praising Re, the dead person then climbs into his boat and heads west—west, in Egyptian mythology, being the land of the blessed dead. Sometimes there’s a spell that has the dead person getting the boat to set sail by naming all the parts of the boat, and the crew who work on it, and the names of the various winds and so on. Once on the boat, the dead person proceeds across the sky and sinks down to the gate of the underworld, kicking off what we’re loosely calling section three of the Book of the Dead. It’s time to go see the big man, Osiris. It’s time to be judged. First, the dead person has to find him.

The underworld in Egyptian mythology is dark and chaotic and perilous, but it’s not a place of unending torment and fire that many of us growing up as Christians might imagine, with little red devils prancing around with forks, while Satan lurks in the deep passages like a Balrog out of Tolkien. It’s a bit more like a dark reflection of the overworld. Barry Kemp explains the variety of the Egyptian Duat this way:

“It possessed mountains, fields, waterways, gates, and sinister ‘caverns’ and ‘mounds’. The landscape was sometimes made of unusual and precious materials: a temple of carnelian, two trees of turquoise, walls of iron around the Field of Rushes.” (Kemp loc. 500)

There were also monsters in these fantastical landscapes – a serpent, for example, that was over 30 cubits (15 meters, or 49 feet and change) in length. Being defeated by any of these monsters would mean instant annihilation, and no afterlife. It’s up to the dead person to pass these places, name them, and name the spirits that lurk in them in order to neutralize the threat they pose him.

Spell 149 lists the names of the fourteen mounds of the underworld and the gods that live in them. Here’s an excerpt from it, in which the dead person encounters that monstrous snake:

“Cover your head, for I am hale, hale, I am one mighty of magic and my eyes have cause me to benefit therefrom. Who is this spirit who goes on his belly and whose tail is on the mountain? See, I have gone against you, and your tail is in my hand. I am one who displays strength.” (Faulkner et. al. 122)

Once beyond the mounds and the caverns, the dead person comes to Osiris’s palace. Like a living Egyptian king, Osiris’s throne room was situated within the heart of his dwelling-place, and the dead person would have to pass a series of gates—usually seven, but sometimes as many as 21, because, again, versions vary. Each gate has a guard, a keeper, and a person to announce visitors. The dead person must know the names of each of these officials and also how to address them. It seems that the best practice here is generally to address them with a lot of bombastic swagger. Here’s part of spell 147 in which the dead person speaks to the officials of the third gate:

“I am the one weighty of striking power, the one who makes his own way. I have traversed, so make a path for me. May you allow that I pass and rescue . . . . the third gate: the name of its gatekeeper is ‘One Who Eats the Putrefaction of His Posterior’; the name of the guardian is “Alert of Face”; the name of the announcer in it is ‘Gateway’.” (Goelet et. al. plate 11)

If I were called “One Who Eats the Putrefaction of His Posterior”, I would not want people saying it out loud very often. I’d let the pushy dead guy through, instead. Some of my other favourite names from this section include:

- He Lives On Worms

- Hippopotamus-Faced

- Eavesdropper

- Seizer of Bread, Raging of Voice (that’s all one name)

- One Who Repels the Crocodile

Kemp suggests that “perhaps” – how academics do love that word, “perhaps” – this procession of gates and guards mirrors how living Egyptians would gain access to the king: by being handed along a chain of officials who asked questions and inspected documents in order to screen out any time-wasters or potential assassins. (Kemp loc. 524) At any rate, once the dead person has rattled off all the names of all the people at all the gates, it is time to enter the Hall of the Two Truths, where Osiris waits with a tribunal of 42 divine adjudicators, and face the most important trial of the underworld: the weighing of the heart.

This appears to be the first instance in literature of the idea of judgement after death. You don’t see this in The Epic of Gilgamesh, for example: the afterlife there has a kind of grim equity, in which all the ghosts, regardless of who they were in life, grow wings and dine sadly on dust, unless living people make them regular offerings. Dr. Goelet, in his commentary on The Egyptian Book of the Dead, says that:

“The notion that the deceased shared in the perils and rewards of the afterlife on a nearly equal footing with the deities reveals a striking sense of human dignity, for the Egyptians hoped to become a companion equal of the gods.” (Faulkner et. al. 144)

So this stressful ordeal is actually hopeful. There’s a chance the dead person won’t just evaporate into nothing. Sweet.

Before beginning the trial, the dead person addresses Osiris and the gods of the tribunal. He also gets hyped up by Anubis, the jackal-headed god who will do the actual heart-weighing. In spell 125A, Anubis says:

“A man has come from Egypt who knows our roads and our towns, and I am satisfied with him. I smell his odor as belonging to one among you. He has said to me: I am the Osiris scribe Ani, the vindicated . . .” (Faulkner et. al. plate 30)

In other words: “This guy seems cool.” Then the dead person begins the very long spell known as the negative confession, addressing each of the 42 adjudicators by name in turn. It allows you to get an idea of what moral behavior looked like for the Egyptians, in both everyday life and in terms of religious practice. Here’s a taste:

“O Wide-Strider who came forth from Heliopolis, I have not done wrong.

O Fire-Embracer who came forth from Kheraha, I have not robbed.

O Nosey who came forth from Hermopolis, I have not stolen.

O Swallower of Shades who came forth from Kernet, I have not slain people.

O Terrible of Face who came forth from Rosetjau, I have not destroyed the food offerings.” (Faulkner et. al. plate 31)

Other things the dead person has not done include messing with weights and measures, discussing secrets, making bad land deals, fornicating with married women (that’s in there twice), and raising his voice. Some of these are moral precepts, but many of them seem to be on the order of—well, not of party fouls, exactly, but lapses of etiquette rather than sins. I’m reminded of what Richard Parkinson, the translator of the Tale of Sinuhe, said in his introduction about the Egyptians being essentially pessimistic, conservative, and anxious about preserving social order. This is very much a vision of the afterlife shaped by a class of bureaucrats.

At any rate: once he has denied all these various wrongdoings, it’s time for the dead person to put his heart on a scale opposite the Feather of Truth. He speaks one last spell before this, ordering his heart not to betray him – that’s the text I read out at the top of the episode, spell 30B – and the weighing begins.

Anubis places the heart in the scale. The official judge of the proceeding is the god Thoth, who has the head of an ibis and is usually shown writing in a book or on a tablet. Squatting behind Thoth is the very unpleasant goddess known as Ammit the Devourer. She is part crocodile, part jackal, and part hippopotamus, and in my edition of the Papyrus of Ani she also appears to be wearing a wig. She is looking up at Thoth with a tense, hopeful expression I have glimpsed many times on my cat’s face – usually when I am carving a roast chicken. Should the dead person’s heart fail the test, it will be fed to Ammit and the dead person will go poof out of existence forever.

However, our dead person knows all the names and all the things to say, so he is of course vindicated. Thoth speaks:

“Hear this word of very truth. I have judged the heart of the deceased, and his soul stands as a witness for him. His deeds are righteous in the great balance, and no sin has been found in him.” (Faulkner et. al. plate 3)

The gods of the tribunal declare themselves satisfied with Thoth’s judgement, and the dead person is brought before Osiris by Horus, where he is permitted to partake of the bread and beer offered to Osiris. He is now a member of the blessed dead, and will remain among the great powers of the universe for eternity.

That’s about as good a summary of The Egyptian Book of the Dead as I can give you. I think it’s probably inevitable that something so old and so changeable would feel alien to me as a reader. But I feel like it’s also alienated from human emotion in some ways. I recognize the fearful landscape of the underworld – humans trying to make sense of what happens after death, and groping for ideas already familiar to them – but there’s no reference, outside of the negative confession, to who the person was before he died.

There’s no effort to preserve that identity. There’s only this preoccupation with obtaining a high-status identity among all these gods and spirits. I think it’s very telling that there’s nothing in The Book of the Dead that can help the deceased visit loved ones who might be mourning him in the world of the living. There are no spells to help him reunite with loved ones who died before him. It’s beautiful and mysterious, but fundamentally quite cold. If I were offered the chance to live forever but not be surrounded by those I love, I would honestly prefer to become a snack for Ammit the Devourer.

If you decide you want to have a go at reading the Book of the Dead for yourself, I recommend you get a big, illustrated coffee-table version (or borrow one from the library). The artwork is so important to appreciating The Book of the Dead. I was able to pick up a 1998 edition with large, full-color reproductions of the Papyrus of Ani from a used book shop for about $13 (that’s a tenner in the UK). And, speaking from personal experience, if you have an artsy kid in your house who’s at all into the Egyptians, they will really enjoy leafing through this book even before they can read it. Absolutely do not get a text-only version – particularly E.A. Wallis Budge’s version, which Goelet calls “quite antiquated.” (Faulkner et. al. 16)

Budge! So far with this show he’s drawn the most messages and comments from those of you listening. You all despise him. I live to serve, so he’ll be back next time in episode six: The Egyptologist and the Magicians, in which we look at how his work on Egyptian mythology and magical practices influenced late 19th-century occultists, particularly Aliester Crowley and his frenemies in the Order of the Golden Dawn. That’s coming to you on Thursday, May 9th.

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

Wilkinson, Toby. A World Beneath the Sands: The Golden Age of Egyptology. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2022.

The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Being the Papyrus of Ani. Trans. by Raymond O. Faulkner and Ogden Goelet, Chronicle Books, 1998.

Kemp, Barry J. How to Read the Egyptian Book of the Dead. W.W. Norton & Co., 2008.

“In Our Time.” The Egyptian Book of the Dead, presented by Melvyn Bragg, BBC Radio 4, 27 Apr. 2017.

Leave a comment