“The two disciples sang the poem, which is replete with all the poetic sentiments: the humorous, the erotic, the piteous, the wrathful, the heroic, the terrifying, the loathsome, and the rest.” (The Ramayana of Vālmīki, Goldman 57)

The charioteer’s hands and forearms throbbed as he sat counting arrows. The day’s fighting had ended hours ago, but the ringing war-cries and the shrieks of the wounded still resounded in his brain—sometimes to the point of disturbing his counting. He was grateful to have lived to return to camp, but weary of the many tasks expected of him.

After the chariot had rolled to a stop he had barely had time to take more than a little water and dried fruit before plunging into his duties. He’d wiped the sweat from the horses’ flanks, seen to their wounds, and fed them. He’d removed his master’s armor and scoured it with sand. He’d looked over his master’s body, cleaned the cuts and noted the bruises. Then he had carefully massaged his master’s muscles, taking pains to work his knuckles into all the scaffolding of the shoulders which supported the princely bow arm: the long muscle from the neck, the meaty cap of the shoulder, and the many little muscles that knit the shoulder to the spine.

When his master was washed and dressed, the charioteer had then turned to maintenance. He’d pulled arrows out of the chariot, reseated a wheel hub that had been almost knocked away from the axel, and replaced pieces of the harness. Then came his least-favourite duty: fletching arrows. Trimming the feathers, crowding around the glue pot with the other charioteers, smelling the glue, scalding his fingers on the hot glue—these were the unglamourous, tedious tasks which laid the foundation for acts of heroism.

But there was one task he never minded: the last task he had to complete every night. As the camp settled down and the watches were set, he and the other charioteers would gather around the fires and sing of the greatest of all heroes. They sang of the lotus-eyed prince of Ayodhya, the incarnation of Vishnu on earth: they sang of Rama, tiger among men.

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time.

Introduction: The Hindu Epics

Books of All Time is a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode 42: Valmiki, The Ramayana, Part 1 – Tiger Among Men. As always, if you want to read the transcript of this episode or see the references I used to write it, you can visit our website, www.booksofalltime.co.uk. There’s a link in the show notes if you need it. Let’s begin.

This week we return to the Indian subcontinent for a much-needed break from philosophy—much-needed for me, at any rate—to dive into the first of two Sanskrit epics on what remains of our reading list this year. Contrary to what I said at the end of the last episode (thanks to listener R. for reaching out and setting me straight on my chronology), we begin not with the Mahabharata, but with the Ramayana. Traditionally attributed to a venerated poet named Valmiki, the Ramayana seems to have started taking form as a written work from about 350 BCE.

It’s probably much older than that, however. Scholars who have analysed its linguistic style reckon that portions of the Ramayana could have been composed as early as 700 BCE, possibly around the same time the Iliad and the Odyssey were taking shape in Greece. Note well, however, that many Hindus and other people from Asia believe the Ramayana is older than the Iliad, and may even have influenced it. There are quite a few plot points in common: a kidnapped wife, royal brothers sent to retrieve her, a bloody series of battles before the walls of a city, divine intervention.

Like the Iliad and the Odyssey, the Ramayana also shows all the signs of having begun as an oral poem to be recited. The little military-camp vignette I opened the show with is based on the American scholar Wendy Doniger’s description, in her book The Hindus: An Alternative History, of one context in which the Ramayana and its brother epic, the Mahabharata, might have been performed.

And oh, man, is this a story worth performing. It’s very long—at approximately 48,000 lines of poetry broken into seven books, it’s about three times as long as the 16,000-line Iliad—and packed with amazing action. I was able to read an abridged version of the 19th-century verse translation by the Indian scholar Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848-1909) published by Macmillan and just about got through a full-length prose version edited by Robert Goldman and Sally Sutherland Goldman for the Princeton Library of Asian Translations. I will not be reading two translations for the Mahabharata, however, because it is even longer—at 100,000 lines and over a million words, it’s the longest epic poem known anywhere in world literature. I’m chewing my way through an abridged version of it.

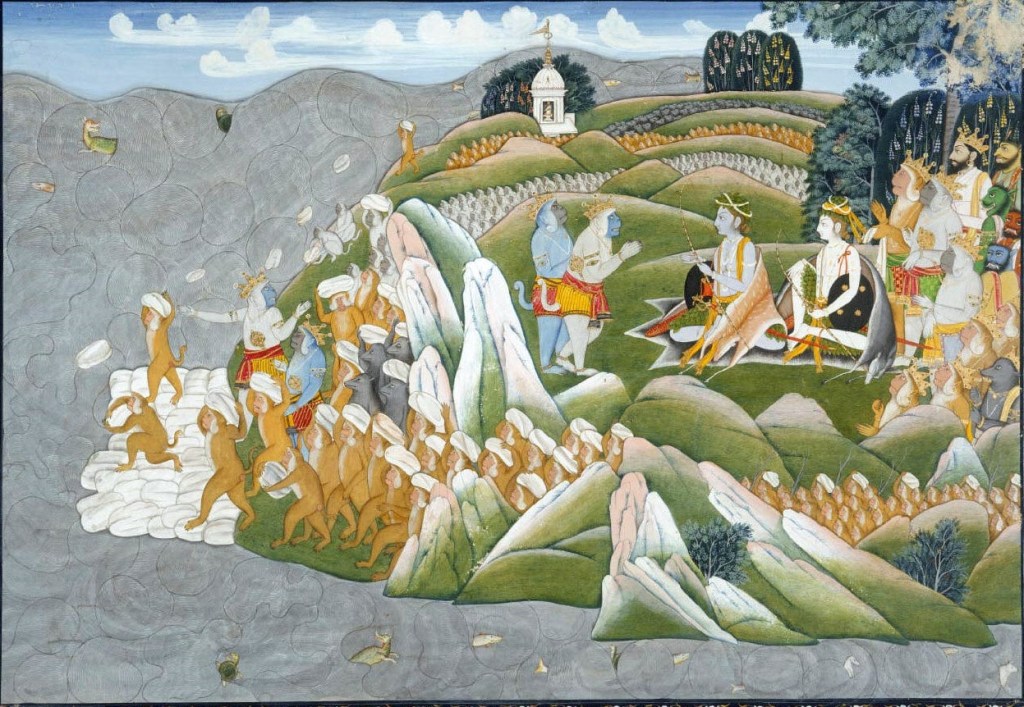

Anyway. The Ramayana. It’s the story of Rama, prince of the Kosala kingdom and an avatar of the god Vishnu, and his trials and tribulations after he is cheated out of his inheritance and sent into exile. His story has magic, adventure, single combat, enormous battles, vicious demons, wise sages, noble monkeys, scheming ladies’ maids and an incredible heroine, the princess Sita. Unlike the Iliad, which focused on stories of heroism in the face of divine meddling, the Ramayana is about virtue in the face of suffering–though there’s plenty of heroism to go around, too, and a more benign sort of divine intervention.

The Ramayana is also more varied than the Iliad in that it doesn’t focus on a specific time and place. It covers the entire sweep of Rama’s career from birth to manhood, from his father’s marvelous city, Ayodhya, to the forests where he is exiled and to the island where his forces clash with the hosts of the demon king Ravana. The characters include humans, animals, demons, and gods, and there are interesting digressions about spirituality, about dharma, righteousness, and adharma, immorality.

Within Hinduism, the Ramayana is considered a holy work, though not a scriptural work like the Vedas or the Upanishads. Instead, it’s classified as itihasa, “historical narrative”. Reading, memorizing, and reciting the Ramayana has spiritual benefits for practitioners of Hinduism. The characters within it can be seen as examples of how (or how not to) live virtuous lives. It is full of colour and light and song and it is exactly what I needed after being stuck in that dining room with Socrates and his hangers-on for over a month.

And maybe it’s exactly what you’ll need, too. There’s more to be said about the immense influence of the Ramayana on the literature of Asia, but it can wait until the end of the episode. So without further ado, let’s jump into the story.

Part 1: Beginning to Abduction of Sita

We open in a forest, where the poet and holy man Vālmīki is visiting some sages at an ashram, a religious community. These ashrams were full of ascetics, that is, people who were renouncing material and physical comforts to live a monastic life of spiritual contemplation. We’ll talk more about the reality of these communities and the religions that were springing up in the Indian subcontinent in the next episode, but know that these secluded ashrams and the sages who live within them are a recurring feature in both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata.

Vālmīki asks the head of the ashram if there are any virtuous men left in the world—a perpetual anxiety in any era, apparently. “Oh yes,” the sage tells him, “King Rama.” The sage then launches into a full-on, spoiler-filled summary of the story we’re about to hear. Once the sage has finished, Vālmīki goes off into the woods to ponder everything he’s heard and find a place to take a ritual bath. As he is walking along a river with his attendant, he sees a pair of cranes performing a mating dance. He stands watching in rapture until suddenly the male crane is shot by a hunter.

Vālmīki cries out in horror and grief. He reprimands the hunter and eulogizes the bird in a rhymed couplet, serendipitously inventing a new type of poetic meter (or, according to the prose retelling, inventing poetry itself). At any rate, the god Brahma appears to Vālmīki at this point, impressed with his improvising, and commands him to use his new styling to tell the tale of Rama in full. And so the story proper begins.

In the kingdom of Kosala, in the city of Ayodhya, there is peace, prosperity, and harmony. We hear how everyone, from the highest priest to the humblest worker, is virtuous and hard-working and intelligent under the reign of good king Dasaratha. There’s a delightful quote from the prose version:

“Nowhere in Ayodhya could one find a lecher, a miser, a cruel or unlearned man, or an agnostic . . . There was no one who had unclean food or was ungenerous. . . . No one was lacking in either rings or self-control.” (Goldman 58)

The only thorn in this bed of roses is that Dasaratha lacks a son to inherit his estate. On the advice of his priests, he begins to prepare for the royal horse sacrifice. You may (or may not) remember from last year’s episodes on the Rig Veda that this is a process which takes a year to build up to – setting up the sacrifice site, choosing a horse and feeding it correctly, etc.

When the sacrifice finally does happen, we cut, as in Homer, to the realm of the gods. The vedic pantheon, however, is not involved in nearly so much Real Housewives drama as the Olympians are. Instead, while they are queuing up to get their share of Dasaratha’s offering, the gods are engaged in a serious discussion. They are debating what to do about Ravana, the king of the rakshasas–the demons.

Apparently, Ravana had once managed to impress Brahma, the supreme god, and received a boon from him. This boon made him invulnerable to gods, other demons, the gandharvas—supernatural musicians who work for Indra—and other divinities. Now the gods are irritated, because Ravana is wreaking havoc and they can’t do anything about him.

“Ah,” says Brahma, “the solution is simple! He forgot to ask to be made invulnerable to men. Simply find a man to kill him.”

This is easier said than done: Ravana has ten heads and ten sets of arms, and is a formidable warrior who commands a host of similarly fierce demons. So the gods decide that one of their number should descend to earth in the incarnation of a man to put Ravana in his place—and oh, how convenient, here we are lined up to partake of a sacrifice by a good, virtuous king who wants sons. It’s settled that Vishnu should be the one to go.

Now, there are many gods in Hinduism, and there are many shades and traditions within Hinduism which treat those gods in many different ways. What I’ve gathered from the introductions to both my editions of the Ramayana is that Vishnu is generally seen as a protector of righteousness—a god of preservation. He’s also considered part of a trinity along with Brahma, the god of creation, and Shiva, the god of destruction.

While you’d expect a lapsed Catholic like me to hear the word “trinity” and compare it to the Christian one, what I really am reminded of here is the relationship between Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades—but only a bit. Poseidon isn’t any kind of match for Vishnu in terms of what he stands for, and none of the Olympian gods are what you could call virtuous.

Anyway, Vishnu agrees to go. He immediately sends a servant to appear to King Dasaratha and his priestly attendants. This servant materialises in fierce and glorious form in the sacrificial fire. From the prose version, we have this description:

“There arose from the sacred fire a great being of incomparable radiance, enormous power, and immense might. He was black and clothed in red. His mouth was red, and his voice was like the sound of a war drum. The hair of his body, head, and beard were as glossy as that of a tawny-eyed lion. He bore auspicious marks and was adorned with celestial ornaments. His height was that of a mountain peak, and his gait that of a haughty tiger.” (Goldman 69)

This attendant offers King Dasharatha a beautiful golden vessel containing some “celestial porridge,” and instructs him to give it to his wives. Dasharatha has three wives, and he trots off post-haste to share the porridge with them. To his principal wife, Kausalya, he gives the lion’s share of the porridge. His next wife, Sumitra, gets a medium portion, and his third wife Kaikeyi gets the remainder. All three women have boys: Kaikeyi’s son is Bhatra, Sumitra has twins, Lakshmana and Satrughna, and Kausalya gives birth to Rama, who is the eldest and most glorious of the four. Each child has supernatural graces proportionate to the amount of porridge his mother consumed.

The boys flourish, studying scripture, learning the arts, and practicing religious devotions with fervour. When they are teenagers, they go to help the sage Vishvamitra cleanse his sacrificial space from evil demons. Upon defeating the demons, the boys—in particular Rama—are given many legendary weapons and mantras—spells for charging weapons with holy power—that they will be able to call upon later in life.

After traveling with and learning from Vishvamitra, Rama and his brothers return home to Ayodhya, when they are told that they are to attend a fire sacrifice in a neighbouring kingdom: Videha, ruled by King Janak. Upon arrival in Videha, Rama learns that Janak has two treasures: one, an enormous magical bow known as the Bow of Rudra, god of storms. The other is a beautiful daughter, Sita. Sita is actually the daughter of the earth goddess Bhumi. Janak discovered baby Sita curled up in a furrow while performing an agricultural rite that involved plowing a field.

This divine daughter won’t be married off to any old prince; instead, Sita can only be won by the man who can bend, string, and fire an arrow from the Bow of Rudra. (And yes, this is a plot point in Homer’s Odyssey as well—if you missed last year’s episode on the interesting connections between Ancient Greece and Ancient India, do give that a listen; it’s episode XXX.) In the poetic version, we hear that:

Gods before the bow of RUDRA have in righteous terror quailed,

Rakshasas fierce and stout Asuras have in futile effort failed,

Mortal man will struggle vainly RUDRA’S wondrous bow to bend,

Vainly strive to string the weapon and the shining dart to send,

Holy saint and royal rishi, here is Janak’s ancient bow,

Shew it to Ayodhya’s princes, speak to them my kingly vow!”

(Dutt 18–19)

Naturally, being an avatar of Vishnu, Rama is more than equal to the task of bending, stringing, and firing the bow of Rudra. A wedding is arranged, and with royal splendour all the sons of Dasharatha marry a daughter or niece of king Janak. Upon returning to Ayodhya with their brides, the brothers split up: Rama and Lakshman stay in Ayodhya, while Bharat and Satrughna go to visit Bharat’s grandfather, Kaikeya. Rama, meanwhile, steps up to assist his father in the governance of Ayodhya. He is described as a renaissance man of the highest order:

“Only after satisfying the claims of righteousness and statecraft would he give himself up to pleasure, and then never immoderately. He was a connoisseur of the fine arts and understood all aspects of political life. He was proficient in training and riding horses and elephants, eminently knowledgeable in the science of weapons, and esteemed throughout the world as a master chariot-warrior.” (Goldman 131)

He is also described as kind to his subjects—dismayed when tragedy befalls them, delighted when there’s cause to celebrate. The guy is a marvel. And Dasharatha is getting older. He decides to officially declare Rama as his prince regent. His advisors and the people of the city are all pleased with this, but he is troubled by one thing: inauspicious dreams.

He has seen lightning and meteors and destruction. His court astrologers say that there are ominous planetary conjunctions happening. Still, he decides that the investiture needs to happen–and needs to happen right away. He commands Rama and Sita to fast and pray: Rama will be consecrated as prince regent the very next day.

The preparations begin that night, and while many of the cityfolk are rejoicing, there is one who is not: Manthara, a hunchbacked woman in the service of Rama’s stepmother Kaikeyi, who is Bharat’s mother. Manthara goes and drips poison in Kaikeyi’s ears about Dasharatha’s decision to elevate Rama. It’s not merely an honour for Rama, Manthara argues: it’s a threat to Kaikeyi’s status and to the status of her son, Bharat.

Kaikeyi, to her credit, dismisses these ideas at first, but Manthara persists. She wins Kaikeyi over by reminding her that Dasharatha owes her: years ago, Kaikeyi was present at a battle where Dasharatha was mortally wounded. She pulled him off the field and personally tended to his injuries, saving his life. He granted her the right to ask any two requests that were within his power to fulfil, and she still hasn’t cashed those in.

Tell him that you want Bharat to be prince regent, says Manthara, and that you want Rama banished into the forest. Not for life, just for, oh, say, 14 years. That should give your son enough time to consolidate his power so that when Rama returns, he can’t threaten Bharat’s reign. Kaikeyi is won over by this. Her speech of praise to Manthara is, uh, really something:

“And this huge hump of yours, wide as the hub of a chariot wheel—your clever ideas must be stored in it, your political wisdom and powers of illusion. . . . When I have accomplished my purpose, my lovely, when I am satisfied, I will anoint your hump with precious liquid gold.” (Goldman 141)

Very bold sartorial strategy there, Kaikeyi—emphasize the lady’s most prominent feature and dare people to hate on it.

At any rate. Kaikeyi removes all her jewelry, dresses in rags, and lies on the floor, beginning a hunger strike. When Dasharatha comes to visit her, he’s alarmed to see her in this state. When she tells him what she wants, he is distraught. He has to choose between giving up his integrity—he did promise his second wife these boons, and did so before witnesses—and his eldest son’s inheritance.

In the morning, hours before the ceremony of investiture is to begin, Dasharatha summons Rama to him. But the king is unable to pronounce the sentence. Kaikeyi does it for him:

“Wounded erst by foes immortal, saved by Queen Kaikeyi’s care,

Two great boons your father plighted and his royal words were fair,

I have sought their due fulfilment,—brightly shines my Bharat’s star,

Bharat shall be Heir and Regent, Rama shall be banished far!

If thy father’s royal mandate thou wouldst list and honour still,

Fourteen years in Dandak’s forest live and wander at thy will,

Seven long years and seven, my Rama, thou shalt in the jungle dwell,

Bark of trees shall be thy raiment and thy home the hermit’s cell.” (Dutt 62-63)

Rama takes this calmly—he is a man of immense self-control and he obeys his elders in all things. He assures Kaikeyi he will honor this command. He takes off the sumptuous clothes for his investiture ceremony. He goes to bid farewell to his mother, to his brother Lakshman, and his wife, Sita. Lakshman and Sita, however, are determined not to let Rama go alone. They, too, will share in his exile. Rama is particularly insistent that Sita should remain in the palace and serve his mother. But Sita says:

“For the faithful woman follows where her wedded lord may lead,

In the banishment of Rama, Sita’s exile is decreed,

Sire nor son nor loving brother rules the wedded woman’s state,

With her lord she falls or rises, with her consort courts her fate,

If the righteous son of Raghu wends to forests dark and drear,

Sita steps before her husband wild and thorny paths to clear!” (Dutt 67)

Rama consents to her following. He, Lakshman, and Sita prepare to leave Ayodhya at dawn, accompanied by Rama’s charioteer, Sumantra.

Part 2: Exile and the Abduction of Sita

Although Rama has taken his exile in stride, the common people of Ayodhya have not. News of the king’s sudden change of plans has flown around the city, and when the exiles set out, they’re trailed by a crowd of people begging him not to leave. They follow him all throughout the first day ignoring Rama’s request for them to return home. Rama, anxious that his people not come to harm in the woods, shakes them off by departing before sunup and leaving the main pathways. He does this on foot, sending Sumantra back to Ayodhya with his chariot to tell Dasharatha how he is faring.

We cut back (at least in my abridged poetic version; the prose version has events in a slightly different order) to Ayodhya, where Dasharatha laments the loss of his son and now lies near death. He chalks up his misfortune not just to the unhappy promise he made to Kaikeyi, but to a terrible incident in his youth, which involved him accidentally killing a forest hermit’s son while out hunting. He dies of grief just as Bharata returns from visiting his mother’s kinsmen to learn that he is to take Rama’s place in the succession. Bharata, being a virtuous prince himself, won’t play along with his mother Kaikeyi’s intrigues: he rules as Rama’s regent, placing a pair of Rama’s shoes on the seat of the throne to symbolize that he, too, awaits his brother’s return.

Back to the forest, where Rama, Lakshman, and Sita are disturbed to realize that they are constantly drawing the interest of people who live in the forest and in villages near the river. They stay at the ashram of a sage called Agastya, who directs them to the hill of Chitra-kuta, a place that is remote enough from villages but close to water and teeming with all the fruit and game they will need to survive in exile.

Sita, Rama, and Lakshman head toward Chitra-kuta. On the way they encounter an enormous vulture, who seems to be waiting for them. Rama, expecting the bird is a rakshasa, a demon, confronts it: who are you? The bird answers in a kind voice that he knows who Rama is, and was a friend of Dasharatha’s. He is called Jatayu, and he offers his help to Rama: specifically, he proposes that he act as a guardian for Sita whenever Rama and Lakshman need to go away somewhere. Together they proceed to Chitra-kuta, which is all that Agastya described and more. Lakshman builds them a little cottage to live in, and it seems they have found a peaceful place in which to pass their exile.

There is a lovely description in the full-length prose version of the winter, Rama’s favourite season, spoken by Lakshman. An excerpt:

“Mornings are frosty now, powdered with snow, bitterly cold and windy; the sun is weak, and the wilderness seems empty. . . . [T]he nights pass cold and gray with snow and last far longer than their three watches. As for the moon, all its appeal has passed to the sun. Its disk is misty gray and its glow has vanished, like that of a mirror clouded over by breath.” (Goldman 282)

Of course, things cannot stay peaceful forever: not in a forest where the rakashas roam. A hideous lady-demon, Surpanaki. She prowls around the cottage, and when she spots Rama, she is instantly smitten. Rama addresses her fairly pleasantly, trying to make small talk: who are you, why are you here? Surpanaki immediately shoots her shot:

“What do you want with Sita? She is ugly and misshapen and unworthy of you. . . . I will devour this misshapen slut, this hideous human female with her pinched waist, along with this brother of yours.” (Goldman 284)

Now look, I know that lots of men like the direct approach, but Surpanaki, girl, this is a little too direct. The brothers tease Surpanaki: they suggest that she become Lakshman’s wife instead, or possibly consent to be Rama’s junior wife. Shurpanaki, in addition to having terrible game in the flirting department, also can’t read social cues. She thinks they’re being serious. She declares that she won’t have Sita as a senior wife, and charges at the poor woman, ready to tear her limb from limb.

The brothers leap into action, restraining the demon, and cut off her ears and nose. Surpanaki, howling in pain and rage, bursts free of them and runs away into the forest until she finds one of her brothers, the rakasha prince Khara. On seeing his sister and hearing how she came to be mutilated, Khara sets forth with a demonic host to cut down the brothers. The departure of the host is marked by terrible omens: meteors and rain red as blood, an untimely eclipse and more.

Khara laughs all these off, but perhaps he should have paid more heed: Rama and Lakshman make short work of him and his minions. The forest is thick with dead rakashas. Surpanaki flees yet again, this time to her eldest brother: Ravana, the rakasha king of Lanka, apparently invulnerable to attack, even from the gods.

Ravana vows he will avenge his siblings. But he is more subtle than Khara: instead of an army, he sends a shape-shifting rakasha in the shape of a golden deer to Rama’s ashram, where Sita sees it and is delighted. Lakshman is suspicious of it, but when Sita implores Rama to bring it to her, dead or alive (preferably the latter), he does what a good husband does and goes out after it, ordering Lakshman to stay behind and guard Sita.

After failing to trap it, he shoots the deer with an arrow, and it immediately turns back into a demonic form. It cries out in distress in a voice exactly like Rama’s as it dies.

Sita, hearing this from the ashram, begs Lakshman to go to his brother’s aid. He refuses: he bets this is some demonic trick, and, after all, Rama told him to stay with her. Sita becomes frantic, and accuses Lakshman of disloyalty to his brother:

“Markest thou my Rama’s danger with a cold and callous heart,

Courtest thou the death of elder in thy deep deceitful art,

In thy semblance of compassion dost thou hide a cruel craft,

As in friendly guise the foeman hides his death-compelling shaft,

Following like a faithful [brother] in this dread and lonesome land,

Seekest thou the death of [Rama] to enforce his widow’s hand?” (Dutt 143)

Poor Lakshman is stung by this, and torn—he owes obedience to his brother’s wife as well as to his brother. He leaves the ashram to track down the source of the voice.

This plays into Ravana’s hands. He casts off his usual ten-headed, twenty-armed shape and assumes the appearance of a wandering beggar. He goes to the ashram where Sita waits alone and asks for shelter, which, according to the customs of hospitality, Sita gladly gives him. He asks for her life story, which she gives, and when she inquires about him in turn, he reveals himself in all his terror. At first, Ravana speaks gently:

“But thy beauty’s golden lustre, Sita, wins my royal heart,

Be a sharer of my empire, of my glory take a part,

Many queens of queenly beauty on the royal Ravan wait,

Thou shalt be their reigning empress, thou shalt own my regal state!” (Dutt 149–150)

Sita refuses, and warns him of the danger he’s putting himself in:

“You are seeking to pluck the fangs from the mouth of a venomous serpent or a swift and ravenous lion, the foe of all beasts. . . . You are rubbing your eye with a needle, licking a razor with your tongue, if you seek to violate the beloved wife of [Rama].” (Goldman 318)

He grabs her by the hair and carries her off anyway, flinging her into the back of his chariot, which is drawn by flying donkeys. Jatayu, the vulture, looks up from his perch nearby and gives chase. There follows a pursuit and then a battle, in which Ravana peppers Jatayu with arrows, but can’t bring him down. Jatayu tears apart the chariot and kills the flying donkeys. Ravana falls to earth, clutching Sita. He leaps up and goes for Jatayu with his sword, cutting off the great bird’s wings.

Ravana carries off Sita, flying under his own power to his island kingdom of Lanka far to the south (Sri Lanka, if you’re wondering, the large island off the southeastern coast of India). As they fly, poor Sita cries out for help repeatedly. At one point she sees some monkeys below, and she drops her necklace and scarf in the hopes that the monkeys will find them and take them to Rama.

Then Sita is whisked across the Palk Strait to Lanka, where Ravana imprisons her in his fabulous palace heaving with treasure and ferocious demon servants. He tries to persuade her to sleep with him, but Sita refuses. You do not, under any circumstances, have to hand it to Ravana, but it is to his credit that he doesn’t force himself on her. Instead, he tells her that if she does not willingly come to his bed in the next two months, he’ll chop her up and eat her. So she’s got that going for her.

Back in the forest, Rama and Lakshman have found Jatayu, bleeding out near the wreckage of Ravana’s chariot. With his dying breath, he tells them what happened to Sita. The brothers weep over Jatayu and cremate him. Then, they strike out southward in pursuit. Along the way they encounter another rakasha, Kabandha. He explains to Rama and Lakshman that he is cursed, but if they free him from his curse by killing him and cremating him, he will assume his true form and advise them how to defeat Ravana and get Sita back.

The brothers do this, and then, quote:

“The body of Kabandha melted, for it was solid fat, like a lump of butter. But then suddenly, shaking the pyre, he ascended like a smokeless flame, a mighty creature wearing spotless garments and a heavenly garland. With a sudden rush he flew up in delight from the pyre, luminous and dressed in immaculate raiment.” (Goldman 345)

In his new, liberated form, Kabandha is able to peer into the future and foresee that the brothers cannot defeat Ravana on their own. They must make an alliance. Kabandha urges them to go to Lake Pampa to find Sugivra, king of the apes, who is in need of help. If the brothers can assist him to secure his throne from a usurper, says Kabandha, he will become their staunch ally. Rama and Lakshman thank him, and as his spirit departs, so do they.

Part 3: Divine Monkey Business

Rama and Lakshman arrive at Lake Pampa, which is in a valley high in the hills. Sugriva is watching them from one of the hilltops, and he’s suspicious: he expects they are spies sent by his brother, Vali the usurper. He asks his right-hand monkey, the mighty Hanuman, son of the wind god Vayu, to go scout out these strangers and report back to him.

Hanuman leaps down from the hill and greets the brothers. They immediately form a mutual admiration society: Hanuman is wrung with pity about their story of exile and the loss of Sita; Rama and Lakshman are sorry to hear that Sugriva has lost his throne and his queen to his brother. Hanuman escorts them to his king, and they seal their alliance. Sugriva will challenge his brother to single combat, and Rama will be his second.

They go to the monkeys’ royal city of Kishkindha. Sugriva calls out Vali, and, after some smack-talk and chest thumping, the two ape-lords clash:

“Like the sun and moon in conflict or like eagles in their fight,

Still they fought with cherished hatred and an unforgotten spite,

Still the wrathful rivals wrestled with their bleeding arms and knees,

With their nails like claws of tigers and with riven rocks and trees.” (Dutt 163)

These guys are going at it–flinging trees and boulders at each other, biting and clawing. It seems at one point that Vali has the better of Sugriva, and that’s when Rama steps in and fires an arrow. Vali falls. Sugriva is able to take his throne. To Rama’s annoyance, the monkey-king makes him wait until after his coronation and the monsoon rains before keeping up his end of the bargain. Monkey scouts head out in all four directions with orders to spend the next month searching for news of Sita, and Sugriva promises Rama that, when the time comes to battle with Ravana and his demons, he will provide millions upon millions of monkey warriors.

Hanuman, who is now deeply devoted to Rama, goes south, carrying a ring Rama has given him to show to Sita if he finds her. He and his monkey companions spend ages searching the mountains and forests, fighting snakes and fording rivers. They get stuck in a cave, and when they are finally helped out of it by a kindly lady hermit, they realise their month is nearly up. Fortunately, a chance encounter with another giant vulture, Sampati, gives them the intel they need: Sampati saw Ravana flying to Lanka with Sita writhing in his horrible grasp.

Getting to Lanka is a problem: ordinary monkeys can neither swim nor leap that far. Fortunately, Hanuman is on the case. Tapping into the divine power given to him by his father, he grows to a titanic size. As he crouches to leap across the sea, his feet crush the mountain on which he stands, toppling trees, sending creatures running or slithering or flapping for safety, exposing deep veins of gold and silver. When he launches himself upward, blossoming trees cling for a while to his fur. The full-length version gives a loving account of his shadow on the waters of the strait, of the sea-birds scattering before him and wind rushing through his armpits–you would think Valmiki had once leapt across an ocean himself, the description is so detailed.

As Hanuman’s flight continues, he is tested by the gods of the ocean. First they send up a mountain laden with food for him to rest on. He demurs–he’s got to get to Lanka. Then they send a great sea serpent to threaten to eat him, but he eludes her. Next a demon grabs hold of his shadow as he flies past, and nearly swallows him–but Hanuman shrinks himself down to a tiny size, drops into the monster’s gullet to slice up its vital organs, then flies out again. Expanding again to an enormous size, he finally lands on Lanka, where he swiftly runs inland to Ravana’s palace.

Impressed as he is by the demon-lord’s domain, which is as ornate and beautiful a pleasure-dome as one could wish for, Hanuman is also dismayed: the place is an unassailable fortress, even for millions of monkey warriors. He files that away and continues looking for Sita, climbing through a series of nested, flying palaces and searching through innumerable harems, galleries, and treasure-rooms. He is beginning to despair that she must have been killed, and then, suddenly, he finds Sita in a garden, closely watched by ten fierce demon women.

Sita has been going through it. She is frail from fasting, still wearing the same garments Ravana brought her to Lanka in–now worn and dirty. The prose version describes her like this, quote:

“She looked like the shining sliver of the waxing moon. Her radiance was lovely; but with her beauty now only faintly discernible, she resembled a flame of fire occluded by thick smoke . . . . She had a single braid—like a black serpent—falling down her back.” (Goldman 459)

Hanuman watches from a tree as Ravana arrives to make his daily request that Sita come and sleep with him. Sita refuses, professing her continued love for Rama, and declaring that Ravana’s days are numbered. Ravana reminds her that it’s her days that are numbered, actually–there is one month remaining before he has her chopped up for his dinner. He leaves, and the rakasha women assigned to watch Sita taunt her horribly for a while.

Hanuman is pretty hilarious–before he takes any decisive action, you get treated to a long internal monologue of his in which he catastrophises about all the things that could go wrong. For instance, when he’s struggling to find Sita, he imagines what will happen if he goes back to Rama and tells him he can’t find her–Rama will die of grief, which means Lakshman will, too, which means their brother Bharat will also die, which will bring calamity to the city of Ayodhya, and so on.

Once Sita collapses in grief, he debates how to approach her in a way that won’t make her immediately suspect him of being a rakasha, too. He also tries to plan how he’ll fight his way out if she does agree to go with him. Will he be able to defeat all the demons? If he does, will he still have the strength to leap back across the ocean with Sita? He decides to approach her by talking in his very best Sanskrit about Rama.

Sita is amazed. She is convinced she is dreaming, but monkeys are bad omens in dreams, and this one seems helpful. After a long speech, Hanuman suddenly remembers the ring Rama gave him, which he presents to Sita. She is overjoyed, but she refuses to go with Hanuman. She tells him only Rama can rescue her. She gives him a comb from her hair to take back to Rama. Hanuman leaves the garden, but not the city.

We are treated to another of his long chains of reasoning: this city will be difficult for Rama to take by force. Hanuman decides to soften the place up a little. He once again grows to enormous size and starts rampaging around, smashing walls and tearing up trees. The demons send companies of warriors at him, including a fair few formidable commanders. Hanuman crushes many of them, but is eventually subdued by Indrajit, Ravana’s son, who is a powerful wizard and captain of Ravana’s forces.

Taken before Ravana’s throne, Hanuman defiantly tells the demon king that Rama will soon come to destroy him. Ravana orders Hanuman to be burned. Once the demons light his tail, Hanuman escapes his captors and runs through the city, setting fires everywhere. After satisfying himself that he has caused destruction to the demons’ defenses, he dips his tail in the ocean to douse the flames, then leaps back across the water to India.

Man, I love that monkey.

Part 4: The Battle and the Aftermath

After rejoining his fellow monkeys (and regaling them with tales of his heroics), Hanuman speeds back to Kishkindha and tells Rama what he learned in Lanka. As the preparations for the battle begin, Rama is overcome with distress about his beloved wife’s predicament. He gets very poetic about it:

“Blow, breeze, where my beloved stays. Touch her and then touch me. For the touching of our limbs now depends on you, as on the moon depends the meeting of our glances.” (Goldman 533-534)

Sugriva tells him to pull himself together: they know she’s alive, they know where she’s held, and Hanuman has already done some softening up of the hard targets. And then they get yet another lucky break: a demon defector arrives at their camp. He is Vibhishana, a younger brother of the wife-snatcher Ravana. He has become disillusioned with his brother’s wickedness, and he offers his service to Rama, along with some valuable intel about Ravana’s plans.

With their leader in better cheer, Rama’s host journeys south to the farthest tip of India. There they encounter a problem: while monkeys can leap across the water to Lanka, men cannot. Rama has no ships. So the monkeys, led by an engineer monkey called Nala, get to building a bridge in the water, carrying innumerable stones and chucking them into the sea, until a narrow path connects India to Lanka.

This is the very charming origin story of an actual geological feature you can still see today: the Rama Setu, or Rama’s Bridge, also known as Adam’s Bridge. It is a skinny chain of limestone shoals that snakes from the southeastern coast of India to the northwestern coast of Sri Lanka, and it is across this bridge that Rama’s army—including Sugivra’s millions of monkeys, Rama and Lakshman with their elephant mounts, and the renegade demon Vibhishana, advances on their enemy.

The clash begins outside the gates of Ravana’s city, as Rama and Lakshman meet the demon vanguard. The fighting is fierce, but the brothers have the upper hand at first. Then Ravana sends out his son Indrajit, who is skilled in magic. His arrival, shrouded in mist, reminds me a little bit of the Witch-King of Angmar in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings:

“Indrajit the son of Ravan, Lanka’s glory and her pride,

Matchless in his magic weapons came and turned the battle’s tide,

Shrouded in a cloud of darkness still he poured his darts like rain,

On young Lakshman and on Rama and on countless Vanars slain,

Matchless in his magic weapons, then he hurled his Naga-dart,

Serpent noose upon his foemen draining lifeblood from their heart!

Vainly then the royal brothers fought the cloud-enshrouded foe,

Vainly sought the unseen warrior dealing unresisted blow,

Fastened by a noose of Naga forced by hidden foe to yield,

Rama and the powerless Lakshman fell and fainted on the field!” (Dutt 201)

It seems that all is lost. Ravana, hearing of his son’s success, bundles Sita into his magic chariot and takes her on a flypast of the battlefield so she can see her husband and brother apparently lying dead. Though distressed, Sita declares that if her husband is indeed dead, he died doing the right thing. And she notes that the monkeys are protecting the brothers as if they expect them to get up and fight again soon.

Ravana flies her back to the palace. And she’s right: the brothers are still alive. There is a great wind from the ocean, and—in another event that calls to mind Tolkien—a great eagle arrives. This is Garuda, the servant and mount of Vishnu. He heals the brothers and they rejoin the fray.

Now comes a long section in which Rama, Lakshman, Sugriva, and Hanuman fight hand-to-hand with a dizzying array of demon underlords. If you read the Ramayana for yourself, you may occasionally find yourself a bit lost in the action. For my money, the best fight is the one between Rama and the mountain-sized demon Kumbhakarna, who only enters the battle after his brother Ravana wakes him up from a nap by having a thousand elephants walk over him.

Kumbhakarna goes crashing into the battle: he cuts a swathe through the monkeys, devouring them, apparently breathing fire at points, and nearly carrying off Sugriva the monkey king. But Rama has his bow and arrows, and the mantras he was taught in his youth. Using these mantras to charge his beautiful arrows, all fletched with peacock feathers, he peppers Kumbhakarna with brutal shots, then severs the demon’s head with one great shot. The head flies into the ocean. The body falls upon the field, crushing millions of monkeys.

Ravana, in despair, sends Indrajit back out onto the field, and the wizard-demon wreaks havoc, crushing the monkey hordes and mortally wounding Lakshman. That night, Hanuman and the traitor-demon Vibhishana walk the field, counting the dead:

“[T]orches in hand, those two heroes, Hanumān and that foremost of the rākṣasas Vibhīṣaṇa, together roamed the battlefront during that night. They saw the ground heaped up on every side with shining weapons that had been dropped and with fallen monkeys, huge as mountains, oozing blood from their limbs and dribbling urine, their tails, hands, thighs, feet, fingers, and necks severed. . . . within the fifth part of a day, Indrajit, self-existent Brahmā’s favorite, had struck down six hundred and seventy million swift monkeys.” (Goldman 642-643)

But even now there is hope. Hanuman is advised by one of the other monkeys that there is a mountain covered in magical healing herbs that can restore the entire army. But it’s in the Himalayas. I pulled up Google Maps, and the distance from Kathmandu, Nepal, in the middle of the Himalayas, to Mannar, a town in Sri Lanka at the end of Ramu’s Bridge, is about 1,800 miles or 3,000 kilometers.

It would seem that the cause is lost. But this is Hanuman we’re talking about. He grows to an enormous size and makes another of his mighty leaps, flying hundreds of miles through the night to the Himalayas. He lands on the mountain of healing herbs. The other monkey had given Hanuman a shopping list of four specific plants to look for, but Hanuman can’t work out which ones they are.

So he does what many a husband sent to the supermarket by a pregnant wife with cravings has done: he decides to bring back an entire selection of things. He tears off the top of the mountain, jumps back in the other direction, and gets the other monkey to pick the herbs he needs.

Lakshman is healed. The monkeys are healed. Hanuman, a conscientious fellow, makes another big leap back and forth to put the mountain back into place before rejoining his companions.

The last surge begins. Rama’s army burns the city of Lanka. Indrajit, in a last-ditch effort to break the enemy’s morale, flies over the army with an illusion of Sita, waving his sword:

“Indrajit arose in anger for his gallant kinsmen slayed,

In his arts and deep devices Sita’s beauteous image made,

And he placed the form of beauty on his speeding battle car,

With his sword he smote the image in the gory field of war!” (Dutt 215)

Seeing his wife apparently cut in half dismays Rama immensely, but Vibhishana, the demon defector, assures him that this is a trick. Vibhishana and Lakshman give chase to Indrajit, and, even though Indrajit has walloped Lakshman twice, they engage in another battle. But you know the saying—third time’s the charm. Lakshman is at last triumphant. He slays Indrajit with an arrow. Rama, aflame with the favor of the gods, goes on a rampage, cutting a swathe through the remaining rakasha forces.

The poet takes us into the demon citadel, where the widows of the demon warriors are wailing and cursing. They very amusingly blame one of their own for all this misery, quote:

“How could that potbellied, snaggletoothed hag Surpanakha have possibly made advances in the forest to Rāma, who is as handsome as Kandarpa, the god of love? Really, someone ought to kill her.” (Goldman 676)

Ravana, being informed of his son’s death, rages through the halls of his palace, ready to cut down Sita—but he decides it would be better to finally rid himself of these brothers instead. He takes to the field, and he and Rama begin to rain arrows upon one another.

Ravana is described as being like a storm cloud; his arrows have the heads of lions and vultures and jackals. Rama’s are likened to meteors, comets, and blazing planets. Javelins are hurled. Both combatants are described as looking like trees in bloom for all the arrows they have sticking out of them. Rama beheads Ravana many times, but, as with the hydra of the Greeks, a new head immediately sprouts in its place.

At last, Rama takes out an arrow blessed by Brahma, fletched with Garuda’s feathers and endowed with virtues of Agni the fire god, Surya the god of light, and Pavana the god of wind. It smites the king of the demons right through the heart, and, quote:

“Heavenly flowers in rain descended on the red and gory plain,

And from unseen harps and timbrels rose a soft celestial strain,

And the ocean heaved in gladness, brighter shone the sunlit sky,

Soft and cool the gentle zephyrs through the forest murmured by,

Sweetest scent and fragrant odours wafted from celestial trees,

Fell upon the earth and ocean, rode upon the laden breeze!” (Dutt 229)

Rama’s forces rejoice and rout the last of the demon host. He and Lakshman ride into the citadel with Hanuman, Sugriva, and Vibhishana. Ravana’s widow comes to Rama, lamenting piteously, blaming her husband for all that has happened. Rama shows her mercy and says that Ravana will be given a proper funeral. He names Vibhishana the new king of Lanka. And he sends for his wife.

You’d expect, after all this time, a joyful reunion. You’d expect the lovers to fall weeping into one another’s arms. But no. Instead, Rama berates his wife—tells her in front of the shocked crowd that he cannot be certain of her faithfulness toward him, that she must have been defiled by Ravana during the time she spent in the demon’s palace. Sita, through tears, tells him off for speaking to her as if she is some vulgar, low woman and not the daughter of an earth-goddess raised in a royal palace.

She demands that Lakshman build her a pyre so she may burn herself upon it. Lakshman looks to his brother, stricken. Rama tells him to obey Sita. The pyre is built, the oiled wood lit. Sita walks around the blaze reverently, then steps into the flames and is swallowed up.

The gods appear. They speak sorrowfully to Rama: why are you acting like a jealous man instead of the god you are? Have you forgotten you are the god Vishnu in the form of a man? “Actually, I sort of had,” Rama admits. Agni, god of the fire comes out of the blaze carrying Sita, who has been transformed from a wasted, unhappy captive to the glorious princess she was in Ayodhya. Now they are reunited properly, and with the gift of a flying palace from Vibhishana, they return to Ayodhya, accompanied by Hanuman.

Rama’s brother Bhatra welcomes him home and happily abdicates the throne for him—the fourteen years have elapsed—and the ten thousand-year reign of Rama begins.

But that’s not quite all.

While Rama is satisfied that his wife has been faithful to him, the common people are not. They didn’t witness the ordeal by fire. They assume that any woman carried off by another man must have been raped—or possibly even colluded in her carrying off. Rama, realizing that his royal legitimacy is at stake because of the stain on his wife’s reputation, again sends his beloved wife away, banishing her forever into the forests.

Sita takes up residence with Valmiki, the composer of the poem. She is pregnant when she arrives, and she bears twin sons in Valmiki’s ashram. The boys, Kusa and Lava, grow into beautiful youths under their mother’s care. Valmiki teaches them the great epic he has written about their father, and sends them to Ayodhya to sing it for the royal court.

On seeing the boys, who present themselves merely as disciples of Valmiki—the disciples mentioned in the passage I quoted at the very top of the show—Rama realizes they are his and Sita’s sons. He is overcome with emotion, and begs them to have Valmiki bring their mother to see him. He declares that Sita should come to court and swear an oath to prove her faithfulness—for real this time.

When she does come, she stands before the great assembly—princes, priests, and courtiers; men and monkeys and gods—and she says:

“If unstained in thought and action I have lived from day of birth,

Spare a daughter’s shame and anguish and receive her, Mother Earth!

If in duty and devotion I have labored undefiled,

Mother Earth who bore this woman, once again receive thy child!” (Dutt 253)

The earth opens. A golden throne rises out of it, resting on the heads of immense snakes. On the throne sits Bhumi, the earth-goddess, who joyfully embraces Sita. Goddess, queen, snakes, throne—all descend into the earth, which closes over them as the gods cry out: “Well done, virtuous Sita!” Rama is left to continue his reign alone, with only the great poem—the first poem, the Ramayana—and his sons to remind him of the woman he loved, fought for, and lost.

Wrap-Up and Outro

There is a very brisk summary, believe it or not, of the first great Sanskrit epic. I’ve treated this as literature, but please understand that it is a deeply holy book for Hindus and many others. I’ve tried not to be too cute about it, because it is as real to the faithful as the events of the New Testament are to many Christians.

In fact, it is possible, today, to literally follow in Rama’s footsteps. Ayodhya is a real place–it’s in north-central India, less than a hundred miles from the border of Nepal–and according to Romesh Dutt, the poetic edition’s translator, people in India can trace almost every stage of Rama’s journeys, from Lake Pampa where he met Sugriva and Hanuman down to Sri Lanka, where he faced and defeated the demon hordes.

I recommend you read the Ramayana. If you have free time over the upcoming holiday—this episode is being released for the first time in early December 2025—you may be able to linger over the full prose version. Be warned that it is big, frequently repetitive (as stories that originate in oral compositions often are), and contains lots of digressions into parables and side quests that I’ve not covered here. Still, who doesn’t like a big, winding epic? Particularly one where fantastic things—especially battles—are described not just once, not even just twice, but at least three or four times in the most lavishly wrought language. And I adore Hanuman, with his heroics and his anxious over-thinking.

If you have less time, do grab the Macmillan edition of Romesh Dutt’s poetic translation. It’s heavily abridged—you don’t get any of the prologue about Valmiki, for instance—and some of the language is a bit clunky to the 21st-century ear, but it is probably about as close as we English-speakers will get to the experience of the Sanskrit edition, which was written in rhyming couplets.

There were many Ramayanas. It went all over Asia, where different regions took it and adapted it differently. In some stories, Sita and Rama wind up reigning happily. In others, Rama never forgets that he’s ultimately divine. The Ramayana was also adapted not just by different cultural and linguistic traditions, but by different religions as well. There’s a Buddhist Ramayana and a Jain Ramayana. These make up the three great religions of ancient India–and much of South Asia–and they’ll be the focus of our second episode on this vast, delightful, thrilling work. Join me next time for Episode 43, The Ramayana, Part 2 – By Means of Every Holy Rite.

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. The Disclaimer Voice of Doom is Ed Brown. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough, John Cole and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also follow us on social media: we’re on Bluesky, Instagram and Facebook. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

- Doniger, Wendy. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Valmiki. Ramayana. Translated by Romesh C. Dutt, Pan Macmillan, 2025.

- Vālmīki. The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India. Edited by Robert P. Goldman and Sally J. Sutherland Goldman. Translated by Sheldon I. Pollock et al., Princeton University Press, 2016.

Leave a comment