“And then I turned such fables of Aesop as I knew, and had ready to my hand, into verse . . . for I reflected that a man who means to be a poet has to use fiction and not facts for his poems, and I could not invent fiction myself.” (Socrates, quoted in Plato’s Phaedrus, in Rourke 11)

She had soaked ink into her sleeve again – good black ink which had taken weeks to make and would now be in short supply for the other sisters in the scriptorium; good black ink which would never wash out of white linen. No matter. Her commission for Count William was complete, and she was pleased with the result. She carefully turned the heavy pages of vellum, with their neat rows of verse. Here was the story of the priest who tried to teach the wolf to read. Here was the Hawk and the Eagle, and the Wolf and the Lamb, retold from Aesop, and here was her own addition, a fable about the Woman Who Tricked Her Husband.

She smiled. Here was the peasant wife, convincing her husband that he hadn’t seen her in bed with another man – after all, here’s his reflection in a barrel of water, and he isn’t actually in the water, is he? It’s all a trick of his mind.

All that was left was to complete the epilogue. She wrote in careful little rounded letters, one curve at a time, in the thin light of some rushes:

“I have given my care and thoughts to inscribing

Something by which, with good attention,

One will be able to rise in worth.

Now learn for yourself, my lord,

How Marie transmitted to us

Some fables of Aesop, which she discovered,

Then wrote them down in verse.

So give heed to what she says.” (Malvern 29)

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time.

Books of All Time is a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode 22: Aesop’s Fables, Part 2: The Moral of the Story. As always, if you want to read the transcript of this episode or see the references I used to write it, you can visit our website, www.booksofalltime.co.uk. There’s a link in the show notes if you need it. Let’s begin.

Welcome back. Following our wild ride through the savage, scatological world of the original Aesop’s Fables, it’s time to figure out how those stories – some of which I felt were unrepeatable on this show – became the wholesome children’s tales most of us remember from our youth. Tracing the evolution of Aesop over time is like tracing the evolution of literature over time – in every age, he means something different, and he often becomes swallowed up by his various interpreters.

In “A Brief History of Fables: From Aesop to Flash Fiction,” the writer Lee Rourke explains that with each subsequent edition of quote-unquote Aesop, “the author [or translator] soon became more important than the fable itself, and it was the author’s interpretation of a fable that was sought by the reader.” (Rourke 27) It’s like each successive interpreter or translator of Aesop puts on an Aesop mask, then tells the fables in their own way for their own purposes. And this process, as we’ll see, begins quite far back.

A brief recap of the Aesop story: we do not know if Aesop actually existed, but tradition has it that he was an enslaved man living in ancient Greece from about 620-560 BCE. The short tales attributed to him began to circulate in oral and written form by at least 450 BCE. We have nothing written by him and no contemporary accounts of his life. In fact, we have no existing editions of Aesop’s Fables in manuscript form prior to the first century CE – so about 700 years after he is supposed to have been born.

According to Laura Gibbs, a scholar from the University of Oklahoma who translated Aesop for Oxford World Classics in 2002, the first mentions of Aesop come from the historian Herodotus (we’ll be getting to know him quite well in a couple of months’ time). Herodotus was writing in the 400s BCE – about 100 years after Aesop supposedly died. He claimed that Aesop was born in Thrace, which spanned parts of modern Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece, and was sold into slavery on the island of Samos. (Gibbs loc. 77)

Gibbs seems to think the evidence points to there being no real written tradition of Aesop during Herodotus’s time – or for a long time afterwards. His fame would have rested totally on an oral tradition, spread by being shared in speeches and personal conversations and drinking parties. “It is very hard for us as modern readers,” she writes, “to appreciate the fact that Aesop could still be an authority even if he were not an author of books to be kept on the shelf.” (Gibbs loc. 116)

Other scholars, however, think there were written collections of Aesop’s fables circulating prior to Herodotus, and that evidence suggests there was one as early as about 320 BCE. This was the conclusion of one B.E. Perry, who seems to be the 500-pound gorilla of Aesop scholarship: virtually every book or paper I’ve looked through for these episodes mentions him or his work, either as something to be built on or something to be moved beyond. Gibbs seems to be in the “move beyond” camp, at least as far as some of his conclusions about sources goes.

Perry wrote a 1962 paper, “Demetrius of Phalerum and the Aesopic Fables” which provides evidence for a collection of Aesop’s Fables gathered in the late 4th century BCE by a Greek scholar named – you guessed it – Demetrius of Phalerum. This collection is lost to us now, but Perry shows that it may have existed as late as the 10th century CE – about a hundred years before the medieval author Marie de France, who starred in my little vignette at the beginning of the episode.

Perry thinks Demetrius’s collection was possibly based on even earlier written copies of fables. For this he cites mentions of Aesop by the philosopher Plato and the playwright Aristophanes, whose lives are pretty well documented, and which were getting started just as Herodotus’s was ending. Both Plato and Aristophanes, Perry explains, saw Aesop not as a teller of moralistic animal fables, but as a teller of aetiological stories rooted in myths. (“Aetiological” is an academic way of saying “origin story” – a myth about how the leopard got its spots, for example, is aetiological in nature.)

Plato was taught by Socrates, and Plato shows us over and over that Socrates knew Aesop’s fables and enjoyed them (this episode started with a quote from Socrates explaining how he was thinking about Aesop’s fables on the eve of his execution). Elsewhere in Plato, Socrates is musing about how pleasure and pain are closely related, and he wonders what kind of fable Aesop would have written to explain the phenomenon – probably something involving pain and pleasure as conjoined twins, he thinks. (Perry 1962, 301). Neat concept, Soc, but maybe flesh it out a little more. Can there be some random violence? Maybe a frog? That’s classic Aesop – dead frogs.

Moving on: There’s an aetiological fable from the anonymous Life of Aesop that Perry thinks may have been a survival from these very early written collections passed on via Demetrius. It’s about the origin of dreams, and I’ll recap it for you quickly: Apollo is very pleased by how successful his temple at Delphi is thanks to the presence of the oracle there. He brags about how his gift of prophecy brings in more offerings than anybody else. Zeus, hearing this, is annoyed: the only reason Apollo has the gift of prophecy is because Zeus gave it to him. So, he decides to teach the pretty boy a lesson.

Zeus endows humans with the ability to dream. What’s more, he gives them true, prophetic dreams, and so business at the temple of Delphi dries up. Apollo, to his credit, is appropriately humbled by this and apologizes to Zeus. Having made his point, Zeus allows humans to keep the ability to dream, but he mixes false ones in with the true ones, and the visits to Delphi soon resume. (Perry 1962, 299)

There’s no moral attached to this story – that’s not the point of it – but if I were writing one, it would probably be “always suck up to Zeus.”

[Music]

So, B.E. Perry traces mentions of Demetrius and supposed fragments of Demetrius all the way to some correspondence between monks in Europe in the 900s – one is writing to the other asking when he can get his copy of Demetrius, and the other monk replies with a clever fable about haste making waste. Whether this lost collection was the link from antiquity or whether it was a figment of several collective imaginations – “wishful thinking,” is how Laura Gibbs describes it at one point – somehow, Aesop survived long enough to be translated into Latin.

The earliest actual, physical copies of stories by Aesop that we have come from the Roman writer Phaedrus, who lived during the early 1st century CE– everything earlier than that just talks about Aesop’s fables, with the occasional fragment, instead. (Gibbs loc. 124) Phaedrus claimed to have been a slave himself, and also claimed that he owed his liberty to the emperor Augustus (again, always suck up to Zeus).

Phaedrus’s edition of Aesop casts his fables into Latin poetry rather than sturdy, relatable Greek prose. Phaedrus is also open about the fact that he’s added a few of his own fables, though he doesn’t tell his readers which ones they are – presumably an ancient Roman audience would have been familiar enough with the “original” Aesop to tell the difference. Phaedrus’s collection also includes the moral tags, positioned at the front of each story (what classicists call a “promythium”).

In his 1965 book, Babrius and Phaedrus, B.E. Perry (again) explains that Phaedrus seems to have been the first interpreter of Aesop to write the fables as entertainment in and of themselves – as something you’d sit down to read for your own enjoyment, rather than as an encyclopaedia of funny little stories to refer to and memorize as appropriate, so you could destroy your opposing counsel during a trial or shut your brother-in-law up during a drinking party. (Perry 1965, xl)

Phaedrus’s work, explains Perry, is the start of “a new epoch in the history of fable-writing and a midway point, as it were, in almost four thousand years of literary practice.” (Perry 1965, xi) The fables of Aesop, once in the hands of Phaedrus and another 1st-century versifier, Babrius, “became an independent form of literature in their own right, instead of a dictionary of metaphors.” (Perry 1965, xii)

Phaedrus’s work also happily ensured the transmission of Aesop and his style of fables in Western Europe, because he wrote in Latin. If you think back to our meta-episode on the Odyssey – that’s episode 12, “Unto a Savage Race” – you may remember that for a time during the Middle Ages, most of literate society in Western Europe had lost the ability to read ancient Greek. Until about the 1400s, the only way most of Europe could engage with Greek classics was through Latin translations. As it was with Homer, so it was with Aesop.

During the early part of the Middle Ages, it’s possible to trace the survival of Aesop via Phaedrus through a number of collections by various writers. These collections frequently pull in fables from other traditions, such as Indian fables or those written by the editors themselves, and they also tend to ping-pong back and forth between poetry and prose. As I was researching this part of the story the names of the various editors began to wash over me a bit – Aphthonius and Avianus, Syntipas and Ignatius Draconius. But then there was one that stood out: a woman, Marie de France.

[Music]

We know almost nothing about Marie de France (though there is a truly wonderful historical fiction novel about her, 2021’s Matrix by Lauren Groff, which imagines her as a subversively creative abbess – go get it if you like crafty nuns and holy visions and things like that). We can infer that she was a literate, well-educated woman – she wrote and presumably spoke in several languages, and was well-versed in French, Latin, and English literature. She was aristocratic, or at least moved in those circles – her patrons included a “Count William,” of whom there were unfortunately many at the time, so we can’t pinpoint hers, and also a “King Henry”, who was probably Henry II of England, the father of both Richard the Lionheart and Bad King John via his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Marie de France’s writing flourished from 1160 to 1215, when she wrote a dozen poems known as lais as well as biographies of both Saint Patrick and Saint Audrey. She also, at the behest of her patron Count William, put together an edition of Aesop’s Fables in French. She is the earliest known woman to have produced a collection of Aesop (she’s also the earliest known woman writer working in French).

In a 1983 paper, the scholar Marjorie M. Malvern points out that Marie’s prologue to her fables – the Ysopet, she called it – dwells on how Aesop’s contemporaries were amazed that an ugly slave could produce such clever tales and compares it to the reception of her own work by men who are amazed a woman can write. (Malvern 28) (Marie also profusely thanks her patron William for commissioning her to write this work – again, always suck up to Zeus.)

According to Lee Rourke, Marie de France quite amusingly claims to have compiled her Aesop not from Phaedrus or another Latin source, but from an English translation produced by King Alfred the Great. This is highly unlikely – while he was certainly unusually learned, he was also unusually busy fending off wave after wave of Vikings to dabble in translations. (Rourke 46)

But this is all by the bye. What matters about Marie de France’s translation of Aesop is that it represents an adaptation of his work for a new age: she wrote, says Lee Rourke, “in a voice that reflected her times . . . observing from within and from afar, whilst mirroring 12th-century culture and society from the courts to the city streets.” (Rourke 47) And a quick scan of her work does bear this out in a few ways: she replaces jackals and camels with wolves and war horses, and scatters priests through the story.

But most importantly, she adds some of her own fables, and these feature human women getting one over on the men who control their lives. These stories, in the true Aesopic tradition, contain bawdy or violent elements, but they add a new dimension of gender tension to the power dynamics. That story about the peasant woman tricking her stupid husband in the opening is a paraphrase of one of her real stories. “Through these delightfully recounted fables,” writes Marjorie Malvern, “Marie makes evident her social conscience and her keen awareness of [the] imperfections present in her own world.” (Malvern 29-31)

Marie preserved the morals – even twisting some of them into punchlines, a la earlier interpreters – but she was still writing for entertainment, and still writing for adults. Aesop as an instructor for children was still several centuries in the future.

It gets rolling with the printing press. While King Alfred’s English translation of Aesop was mythical, the first printed edition of Aesop was, in fact, in English. William Caxton, who introduced the printing press to England during the late 1400s, was passionate about the new technology’s potential as a tool for increasing learning in the population. He also realised it was an excellent business opportunity – printed books sold like hotcakes, relatively speaking. While still an expensive luxury, printed books were much cheaper than hand-illuminated manuscript books produced by specialist scribes. (Rourke 63)

In 1484, Caxton produced an edition of Aesop’s fables that, according to Lee Rourke, “solidified [Aesop’s] presence in English.” (Rourke 64) Caxton’s edition included the moral tags, although intended for adult audiences. It’s also of interest that Caxton’s edition of Aesop (and his printed books generally) contributed to the standardization of written English – which dialect was used, what letters looked like, what punctuation marks were employed, and how different words were spelled. “With Caxton’s press,” writes Rourke, “we can begin to see the emergence of literature as commodity, as something that can be packaged and sold to eager readers.” (Rourke 63)

The last and perhaps greatest collection of Aesop’s fables not originally intended for children was the monumental, 12-volume work by Jean de La Fontaine. La Fontaine was already an established writer in his 40s when the first volume of his Fables appeared in 1668. Until that point, he’d made his name as a slightly disreputable writer of racy stories and verse. Fables, though intended for a sophisticated, adult audience, was his attempt to be accepted as a serious contributor to French literature. It worked a treat.

Volume one of Fables was dedicated to the Dauphin, the six-year-old heir to the throne of France (again, suck up to Zeus, or his kid), and the project was deliberately constructed to teach a moral lesson. In a 1966 paper the scholar Margaret McGowan explains that “[La Fontaine] intends… by the telling of a story to improve man, to widen [man’s] capacity for achieving great things.” (McGowan 266)

La Fontaine’s Fables draw from sources other than Aesop – like Phaedrus and Marie de France, La Fontaine also contributes his own works to the collection. Written in deceptively simple rhyming verse, the Fables have an edge of black humour and subversion. Crucially, they don’t always try to seem ancient or Greek – they incorporate elements of the French society of La Fontaine’s day so he can poke fun at it.

For example, in La Fontaine’s version of The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, the town mouse serves ortolans – little deep-fried songbirds considered a delicacy in France to this day, which you’re traditionally meant to eat while wearing a cloth over your head to hide from God.

La Fontaine’s versions of Aesop have also contributed original metaphors to European culture. One example: he puts a different spin on the fable about the mice who go to war with the cats. Aesop has them dying because some of them decide to wear helmets with horns on them. La Fontaine’s version has only one cat terrorizing the mice. They come up with a plan to put a bell around her neck but spend all their time in council arguing about the best method to achieve this goal. Nobody is actually brave enough to do it. That idea of “belling the cat” – any unpleasant but necessary duty which people avoid – comes to us from him.

“Put simply,” writes Lee Rourke, “La Fontaine’s Fables are an essential piece in the literary jigsaw of the Aesopic tradition and its transition into the realms of modern literature.” (Rourke 68)

From where I’m sitting, they’re also a key step on Aesop’s path into the nursery school classroom: they’re charming, they stay on the right side of respectability, and – this is important – they rhyme. They can be – and were – set to music and seen as entertaining. They also kicked off a vogue for any type of fable that spread all over Europe.

It was 25 years after La Fontaine’s first volume of Fables was published that we finally have a record of someone explicitly making the case to use Aesop’s Fables to teach children. That someone was, of all people, the English political philosopher John Locke – you may remember him if you ever had to struggle through Leviathan, with its famous description of life without government as “nasty, brutish, and short.”

In a 1693 essay, “Some Thoughts Concerning Education,” Locke points out that children seem eager to learn when there’s an element of play involved and that they are naturally curious about animals. When teaching them to read, Aesop’s Fables would be “apt to delight and entertain a child . . . yet afford useful reflection to a grown man. And if his memory retain them all his life after, he will not repent to find them there, among his manly thoughts and serious business.” (Locke, para. 156)

From that point onward, it was off to the races for children’s booksellers and the teachers who patronized their shops. In England, the first edition of Aesop for children was published by the appropriately named Roger L’Estrange, who’d just lost his job as a government censor, during which gig he famously tried to edit John Milton’s Paradise Lost because it seemed a bit down on monarchs.

You can find the text of L’Estrange’s Aesop on the University of Michigan website – I’ve got a link in the transcript – and it is very hilariously misguided as a book for children. Each section includes the fable, followed by the moral, which explains what you just read in the fable. The moral is then followed by a “reflexion,” a kind of mini essay in which L’Estrange explains the explanation of what you read at great length.

Here’s the first sentence of his “reflexion” on The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse (I think it will help if you picture me reading this in one of those long, curly restoration-era wigs):

“THE Design of This Fable is to set forth the Advantages of a Private Life, above Those of a Publick; which are certainly very Great, if the Blessings of Innocence, Security, Meditation, Good Air, Health, and sound Sleeps, without the Rages of Wine, and Lust, or the Contagion of Idle Examples, can make them so: For Every Thing there, is Natural and Gracious.”

Doesn’t every child need to be warned about the rages of wine? Needless to say, L’Estrange’s edition takes all the fun from Aesop and stomps it as dead as a frog in the original Greek fables. No sensible child would be delighted and entertained by this. Still, it was a start. After L’Estrange, more and more editions of Aesop for children began to appear in Britain, France, and elsewhere, until they seemed to be cropping up practically every other year during the 19th century – that era’s version of superhero films, I guess.

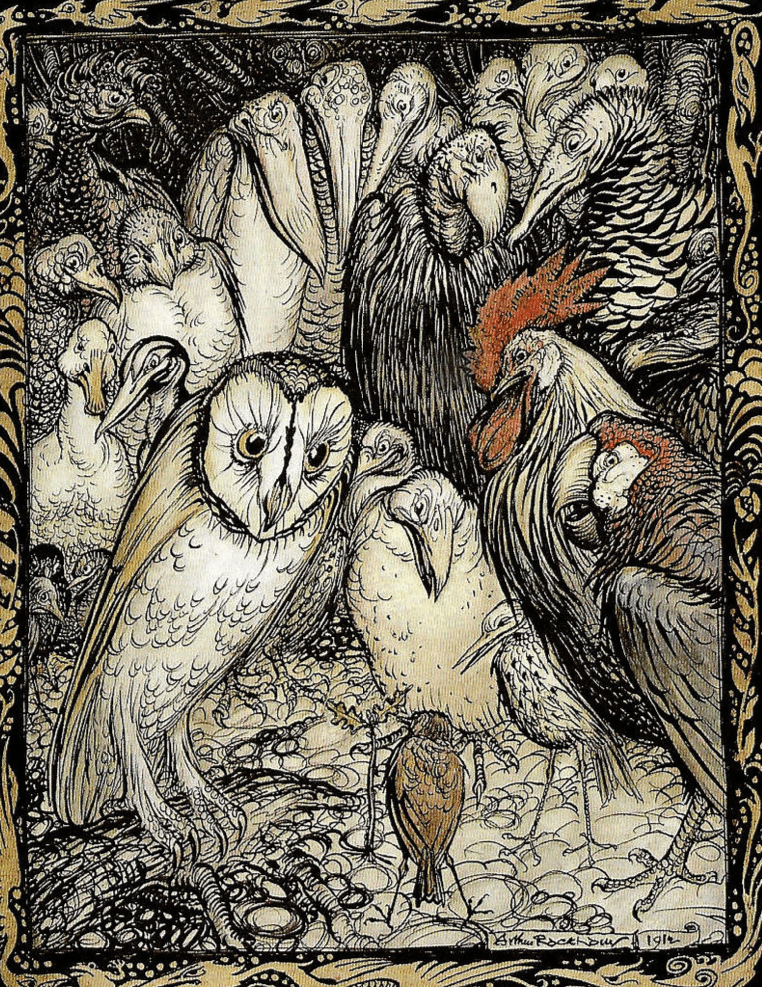

The general trend for these books as time went on was to go with less text and more imagery. Improvements in printing technology almost certainly encouraged this. Many of the great illustrators of the 18th and 19th century put their talents to work in child-friendly editions of Aesop. Gustave Doré did one, as did John Tenniel, most famous as the original illustrator of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

The text also underwent child-friendly refinements. An 1807 English edition of Aesop for children by Richard Scrafton Sharpe, for example, did away with the overlong morals (and certainly with the “reflexions”), instead weaving the lessons into the final lines of the story because, as Sharpe put it, “children, whose minds are alive to the entertainment of an amusing story, too often turn from one fable to another rather than peruse those less-interesting lines” of the moral. (Sharpe 4)

And naturally, the stricter sorts of Christians became anxious about using Aesop, a heathen, as a supplementary moral instructor for their children. (Maybe by that point some of those Christians had read him in the original Greek and were appalled.) Many editions of Aesop strip out any hint of Greek gods or religious practices, and some insert specifically Christian ideas, such as adding an appropriate Bible verse that further illustrates the moral.

And the beat goes on. With each successive incarnation – as picture-book or Bugs Bunny cartoon – Aesop’s Fables moves on to a new generation. Each generation retains the basic idea of a fable by Aesop – funny or odd stories about animals that are meant to teach you something about being human – while losing more and more of their origins in a somewhat alien and savage culture, one where people kept weasels as pets rather than cats, and where it was considered amusing to laugh at a frog’s death.

I am amazed at how far apart my memories of Aesop’s Fables from my own childhood are from the source material. They are, after all, classic stories, and I had always considered classics to be something relatively fixed and unchanging, even if you have to translate them from another language. But it ain’t necessarily so. As Robert Temple put it in his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of Aesop:

“A classic is something which is arrived at by consensus, and the weirder of Aesop’s fables might have destroyed that consensus pretty quickly if anybody but a Greek scholar had been able to read them.” (Temple xvi)

I do wonder what the Aesop who supposedly originated these stories more than two thousand years ago would think of the gentle, sugary children’s tales which now circulate under his name. I imagine he wouldn’t be offended. Probably he’d see the funny side, and possibly he’d observe that if you want to survive for all time, you have to fit yourself to every time. It’s as good a moral as any. Other than “always suck up to Zeus,” of course.

That’s it for this episode. So, I obviously did not read every single edition of Aesop available in researching this week’s show, so I can’t give detailed recommendations if you want to go and read some yourself. La Fontaine’s Fables are widely available, and I have pencilled them in for an episode in the far future, when we get to early modern literature sometime in, I don’t know, the 2030s.

In the near term, I will probably follow up with Marie de France – I have a soft spot for the medieval period – and I will probably also skim some more of L’Estrange’s edition. I’m not sure why, but I find late 17th/early 18th century writing very funny. Those long sentences with all that unnecessary capitalization of nouns, and the long S-es – it’s like listening to your weirdest, smartest friend try to explain something to you while he is very, very drunk.

Next week, we move onto a new genre for this show. We’ve had epics. We’ve had love poems. We’ve had philosophy and history and fables. Now it’s time for prophecy. We’re going back to the Hebrew Bible to read the Book of Isaiah. Join me on Thursday, January 23rd for episode 24: “Isaiah, Part 1: A Voice in the Wilderness.”

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. The Disclaimer Voice of Doom is Ed Brown. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough, John Cole and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. You can also follow us on social media: we’re on Bluesky, Instagram and Facebook. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

Aesop, and Laura Gibbs. Aesop’s Fables. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Aesop, et al. The Complete Fables. Penguin Books Ltd, 2003.

“The Fabliaux of Marie de France.” Harvard University, chaucer.fas.harvard.edu/pages/fabliaux-marie-de-france.

Locke, John. “Some Thoughts Concerning Education.” Bartleby.Com, 13 Sept. 2022, http://www.bartleby.com/lit-hub/hc/some-thoughts-concerning-education/some-thoughts-concerning-education-16/.

L’Estrange, Roger. “Fables of Æsop and Other Eminent Mythologists with Morals and Reflexions.” University of Michigan, quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A26505.0001.001/1:7?rgn=div1%3Bview.

Malvern, Marjorie M. “Marie de France’s Ingenious Uses of the Authorial Voice and Her Singular Contribution to Western Literature.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 2, no. 1, 1983, pp. 21–41, https://doi.org/10.2307/464204.

McGowan, Margaret M. “Moral Intention in the Fables of La Fontaine.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 29, 1966, pp. 264–281, https://doi.org/10.2307/750719.

Perry, B. E. “Demetrius of Phalerum and the Aesopic Fables.” Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, vol. 93, 1962, pp. 287–346, https://doi.org/10.2307/283766.

Phaedrus, and Babrius. Babrius and Phaedrus. Translated by B. E. Perry, Harvard University Press, 1965.

Rourke, Lee. A Brief History of Fables: From Aesop to Flash Fiction. Hesperus, 2011.

Sharpe, Richard Scrafton. “Old Friends in a New Dress; or, Familiar Fables in Verse.” Internet Archive, London: Harvey and Darton, and William Darton, archive.org/details/oldfriendsinnewd00shariala/page/6/mode/2up.

Leave a comment