“When the reader finds himself at a point where the sense is unclear… let him use his head; the gods love riddles, as the ancient sages knew, and those who would converse with the gods must learn to live with and thrive upon riddle and enigma.“ (Doniger 15-16)

On the evening of the third of December, 1872, a learned society of men met in London to hear and to discuss a newly discovered legend from Babylonian literature. These men were philologists and professors, eminent clergymen and politicians—men with pedigrees from the aristocracy, the gentry, or the great institutions of learning. These were men with titles, estates, fleets of servants—in many cases, they were men whom the Queen of England could recognize by sight. They all fell silent as a young, anxious-looking man stood up at a lectern. They leaned forward with interest, waiting to hear what he would share with them, the members of the Biblical Archaeology Society.

The young man had a luxurious beard and a poorly cut suit of clothes. He had never been to university. He had never taken holy orders. Until recently, he had been apprenticed to a banknote engraver, and he lived in three rooms with his wife, five children, and no servants. But through talent, diligence, and luck, he had made what promised to be one of the great archaeological discoveries of the age.

It is possible that just before he began his presentation, the young man locked eyes with a hawk-nosed gentleman with absurd side whiskers seated elsewhere in the room – the Prime Minister of Great Britain and Ireland, William Ewart Gladstone. Perhaps Gladstone tried to give the young man a little encouragement – a kindly twinkle around the edges of his habitual glower, a softening of his scowl. But probably not.

The young man – George Smith – began to read about the discovery he had made while translating a series of cuneiform tablets brought out of Nineveh. It was the tale of a great Babylonian hero who befriended a wild man, defeated a rival tyrant called Humbaba and became king of Uruk before traveling to hear an account of the great flood from Babylonian Noah. Smith was confident that this hero was the same person as Nimrod, the huntsman described in the Book of Genesis, chapter 10: the Bible tells us, after all, that Nimrod was “a mighty one in the earth”, and that he founded both Babel and Erech, which is the same city as Uruk.

The name of this hero given in the tablets, Smith explained confidently, was not Nimrod. It was Izdûmbar. Izdûmbar and Enkidu. Izdûmbar, who saw the deep.

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time.

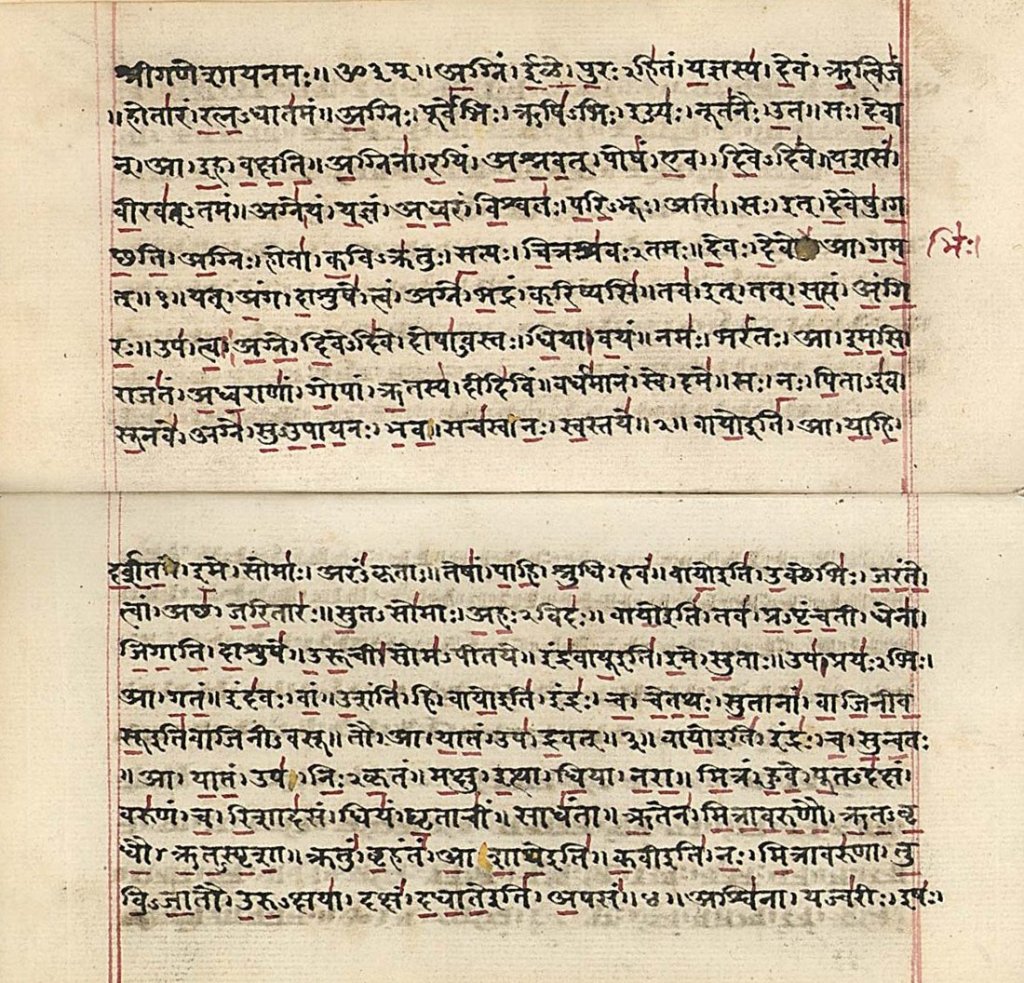

Books of All Time is a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode eight: The Rig Veda, Part Two – Painters, Not Photographers. As always, if you want to read the transcript of this episode or see the references I used to write it, you can visit our website, www.booksofalltime.co.uk. There’s a link in the show notes if you need it. Let’s begin.

Remember George Smith? Way back in episode two, when we were talking about how the Epic of Gilgamesh resurfaced in the 19th century? George Smith was the industrious engraver’s apprentice with the generous lunch break who taught himself to read cuneiform. In 1874, he became the first person in more than 2,000 years to read the Epic of Gilgamesh, and his translation of it wound up shocking the entire western world.

What I didn’t tell you at the time was that George Smith didn’t call the story he’d rediscovered the Epic of Gilgamesh. Instead he called it The Chaldean Account of the Deluge, and its hero, by Smith’s deciphering, was named not Gilgamesh, but Izdûmbar. For nearly 25 years after Smith’s initial publication—long after he’d died from dysentery in Aleppo—people were reading about Izdûmbar, sifting Iraqi sands for more evidence of stories about Izdûmbar, writing long learned treatises about how Izdûmbar could be Nimrod, or possibly could relate to this or that other figure mentioned in the old testament of the Bible.

This mistranslation persisted so long because, as David Damrosch put it in “The Buried Book”, his excellent history of the rediscovery of Gilgamesh, cuneiform writing is “tricky”. It could be used to write any one of four different languages: Assyrian, Akkadian, Ancient Persian, and (the most ancient and most baffling of all) Sumerian. Akkadian alone had more than 600 signs, each of which stood for a different syllable (except when it didn’t). Sometimes the Akkadians used loan words from Sumerian, similar to the way modern lawyers might pepper their English briefs with Latin.

At the time Smith was working, in the 1860s and 1870s, cuneiform in any language had only been readable for about 20 years at best. The whole sum of modern scholarship had barely begun to tease out all its subtleties. Here’s an extended quote from Damrosch’s book to give you an idea of how slippery this type of translation could be.

“The star symbol, pronounced ‘an’, could represent Anu, god of the sky, yet it could also be the first syllable of the pronoun ‘annûtim”, ‘these’, among many other words. (Like many ancient writers, the Mesopotamian scribes didn’t bother to leave spaces between words, so it was always a challenge to decide where a word might begin and end.) Moreover, a symbol could be used for more than one sound, much as in English the letter ‘c’ can have the sound ‘s’ or ‘k’. On the other hand, one sound could be represented by several different characters, much as the letters ‘k’, ‘q’, and sometimes ‘c’ can all represent the same sound, but cuneiform developed with many more complications than are found in simple alphabets. Finally, the individual signs often changed form from one region to another and from one era to the next during the three thousand years of the script’s use.” (Damrosch 26-27)

Damrosch later walks you through how Smith approached his translation. He took pains to puzzle out individual syllables and then connected them to make words, or fragments of words—remember that he was usually working with broken tablets. Smith then used guesswork and assumptions to arrive at his final translation. It was better than anyone had yet managed, but, as I illustrated in the intro to the show, it was still riddled with errors of sound, sense, and fact—errors which were often rooted in his Christian identity, his politics, and in the prevailing ideas of his time. (Damrosch 60-63)

Aside from bringing home the fact that it’s genuinely remarkable we have anything of Gilgamesh at all, this section of Damrosch’s book has stayed with me over the last six months. It’s a little seed putting out shoots of disquiet in my mind: if these scholars could miss so much, what am I missing?

Nearly everything I’m planning to read for Books of All Time over the next several years is a translation—in some cases, a translation of a translation—and if I’m reading something filtered through another person’s consciousness, am I really reading it? How much am I actually grasping? In her introduction to her anthology from The Rig Veda, Wendy Doniger says that translators are “painters rather than photographers, and painters make mistakes.” (Doniger 19)

Even if I could read these books in their original languages—even if I had a complete, pristine set of Gilgamesh tablets to read from, for example—there would almost certainly be great yawning gaps in my understanding based just on the fact that I live in a specific time and place that is very different to ancient Mesopotamia, or Egypt, or northwestern India on the cusp of the Iron Age.

I don’t even have to look outside of my own language to see how rapidly we can lose the broader context of a story. Take the example of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll. It was first published in 1865 and has never been out of print. The broad strokes of the story—girl falls down rabbit hole, encounters many weirdoes—are familiar to nearly everyone. But most 21st-century readers require a specialist annotated edition of the book to understand that virtually every poem in the story is a parody, or to spot the clever digs at politicians or public figures hidden in the illustrations, or to grasp that an obvious pun is also a nerdy math joke.

We have photographs of Lewis Carroll; we have most of his diaries, thousands of letters; we have recollections from people who knew him at the time he was writing Alice. We can reconstruct a lot of the subtext for that story, but really trying to understand it takes work. And that’s a children’s book. With The Rig Veda we are talking about scripture, something that is deeply sacred to millions of people. What am I missing if I read a Western scholar’s translation or analysis of books like this?

It turns out this is something translators and scholars think about constantly. Take the late Gregory Rabassa. He was a translator best known for bringing Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude to English readers (and that’s a life-changing novel, by the way; I think about it with a shudder whenever I see an ant hill). In the opening chapter of his memoir If This Be Treason: Translation and its Dyscontents, Rabassa calls attention to an old Italian saying which apparently was thrown at French translators of Dante by angry Italians who felt they’d butchered the national poem: “Traddutore, tradiatore”—“translator, traitor.” (Rabassa 6)

I always thought translation was a bit like solving a mathematical equation: this equals that. Rabassa says it’s actually more like acting or poetry. But it always involves a series of betrayals, because language and culture are so intimately tied together. “A language,” he says, “will load a word down with all manner of cultural barnacles along the way, bearing it off on a different tangent from a word in another tongue meant to describe the same thing.” (Rabassa 6)

So, for this episode I want to think about some of the problems with translation—and with the analysis that follows it—by looking at two of the major translators of the Rig Veda in English. The first was Friedrich Maximilian Müller – Max Müller to us—who produced the first full-length English edition in the 19th century, and who is considered one of the founders of the scientific study of religions. The second is “our” translator, Professor Wendy Doniger. The former found his work twisted and corrupted by nationalists. The latter has found hers attacked by them.

Max Müller was born in 1823 in the city of Dessau in what was then the Duchy of Anhalt—Germany at that time was a loose confederation of 39 territories that wouldn’t be completely unified until 1871. During Max’s formative years, German culture was awash with romantic ideas about the pure Teutonic past—“pure” in that it was unspoiled by the industrial revolution or capitalism. His family was deeply involved with many romantic musical artists: his father was a poet who collaborated with the composer Franz Schubert; Max’s godfather was the composer Carl Maria von Weber, and growing up he attended school in Leipzig, where he was on socially friendly terms with yet another composer, Felix Mendelssohn.

In spite of all this musical influence, Max took a different path. He earned a Ph.D. in philology—the study of the structure and history of languages, and how they intersect. The languages he mastered on the way to his doctorate included the usual Latin and Greek, but also Persian, Arabic, and—above all—Sanskrit.

In 1888, Müller gave a series of lectures to young men preparing for the Indian Civil Service—young British men, I mean—that was published as a book called India: What Can It Teach Us? In the first lecture, he describes how his mind was well and truly blown the first time a professor told his class that there was a language spoken in India related to German, English, Latin, and Greek:

“At first we thought it was a joke, but when one saw the parallel columns of numerals, pronouns, and verbs in Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin written on the blackboard, one felt in the presence of facts, before which one had to bow. All one’s ideas of Adam and Eve, and the Paradise, and the tower of Babel . . . with Homer and Aeneas and Virgil too, seemed to be whirling round and round till at last one picked up the fragments and tried to build up a new world, and to live with a new historical consciousness.” (Müller loc. 457-465)

The effort to build up and expand on this new historical consciousness drove Müller for the rest of his life. Fortunately, when it came to the study of Sanskrit, he was well-supplied with mentors. While the French had won the race to translate Egyptian hieroglyphics and the English led in the decipherment of languages that used cuneiform, German scholars, in the 19th century, were the West’s major authorities in the study of Sanskrit. It was our old friend Thomas Young (remember him, from episode four? British physician and polymath who dabbled in linguistics) who seems to have coined the term Indo-European languages, but it was Franz Bopp who began the first systematic effort to study and classify the languages in this family group, and he believed that Sanskrit was the oldest sibling.

After earning his Ph.D., Müller went to conduct research with Bopp in Berlin, producing a translation of the Upanishads, a later collection of sacred writings from India. It was during this time that he began to develop his ideas about how language and religion related to and influenced one another. His mentor encouraged him to undertake a translation of the full Rig Veda. Sections of it had been translated, but never the complete set of 1,028 poems. In order to accomplish this monumental task, Müller would need to travel to study manuscripts. Not to India—Müller never in his life went to India—but to London, to the archives of the British East India Company.

Now, I could give you a potted history of the British East India Company, but it is pointless for me to do that when the Empire Podcast exists. The writer and historian William Dalrymple co-presents that show along with the journalist Anita Anand. Dalrymple is the author of an absolutely monumental four-volume history of the East India Company, the first book of which is The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Go and check out Empire and/or those books; they’re well worth your time.

For now, I’ll point out that when Max moved to England in 1846, “the British” who were running India had nothing to do with Parliament or Queen Victoria. “The British” running India then were representatives of a largely unregulated corporation. That corporation was extracting everything it could from India through private taxes, all while suppressing dissent with a private army that, at its peak, included 260,000 mercenaries. Along the way they also confiscated heaps of priceless artefacts, including manuscripts, and brought them back to England for study.

Müller was a charming fella—the historian N.J. Girandot compared him to modern media-savvy academics like Carl Sagan (Girandot 215). He quickly won support from the East India Company for his very large and very expensive Rig Veda project. It took him 25 years to complete it, according to a 1991 article by the scholar Herman W. Tull. This was partly because Müller insisted on including a complex medieval-era commentary along with the text of the hymns, and partly because of that media savvy.

When he wasn’t collating notes and studying manuscripts (or directing his assistants to do so), Müller was busy burrowing into the British academic establishment. He jockeyed for a professorial post at Oxford. He toured other universities to give guest lectures. He accepted armfuls of honorary doctorates and memberships in prestigious learned societies. (When it comes to social climbing, Max Müller could have taught E.A. Wallis Budge a thing or two—sure, Budge wound up with a knighthood, but Müller ultimately landed a place on Queen Victoria’s Privy Council.)

Müller became one of the West’s favorite India Explainers. And reading India: What Can It Teach Us, it’s possible to understand why. Müller is so enthusiastic about his subject. He wears his deep reverence, respect, and even affection for the culture that gave us the Rig Veda on his sleeve. Here he is encouraging those young men to think of their postings to India as a grand adventure:

“Whatever sphere of the human mind you may select for your special study, whether it be language, or religion, or mythology, or philosophy; whether it be laws or customs, primitive art or primitive science, everywhere, you have to go to India, whether you like it or not, because some of the most valuable and most instructive materials in the history of man are treasured up in India, and in India only.” (Müller loc. 294)

Sounds like high praise at first, but mmmm, those two repetitions of “primitive” clang a bit, don’t they? It gets worse. While throughout these lectures Müller repeatedly defends modern Hindus and (most) other Indian people against many of the prevailing British prejudices against them, it’s clear that he romanticized the Vedic cultures of India and regarded everything after 1000 CE or so as a declining or even a degraded society. Tull calls it a “peculiar combination of awe and revulsion in his attitude to India”. (Tull 33)

Personally, I think the awe is a little worse than the revulsion. Mainly because Müller repeatedly uses another word that tends to send people into a defensive crouch—Aryan.

Now. “Aryan” is a Sanskrit word. It’s what the people who wrote the Rig Veda called themselves (their close cultural and linguistic cousins in what’s now Iran also used the word—the name Iran actually derives from arian, which means something like “noble”). To the people who produced the Rig Veda, “Aryan” wasn’t a racial term, it was a cultural one: anybody who knew the hymns and performed the sacrifices and rituals as described in the Rig Veda could become an Aryan.

In 19th-century Europe, however, the word quickly mutated into a signifier of something else entirely. And Max Müller, though not explicitly tied to the odious project of scientific racism, helped accelerate that transformation. Müller and other early Sanskrit scholars from the West took the term Aryan and applied it to every group of people who spoke an Indo-European language. Here are two more quotes from his lectures. The first:

“What then, you may ask, do we find in that ancient Sanskrit literature and cannot find anywhere else? My answer is: we find there the Aryan man, whom we know in his various characters as Greek, Roman, German, Celt, and Slav, in an entirely new character.” (Müller 1268)

The second:

“Sanskrit, and [its] most ancient literary documents, the Vedas . . . can teach us lessons which nothing else can teach . . . the true natural germs of all that is comprehended under the name of civilization, at least the civilization of the Aryan race, that race to which we and all the greatest nations of the world—the Hindus, the Persians, the Greeks and Romans, the Slavs, the Celts, and last, not least, the Teutons, belong.” (Müller loc. 1525)

(I must say, it’s almost touching that he includes the Celts. They don’t usually make the cut for these lists of Übermenschen.)

Müller also promoted the idea that the Vedic peoples were a branch of Northern Europeans who invaded India, and that the qualities which enabled their genius became gradually diluted as they inevitably mixed with the “aboriginals” to the south. Modern Hindus, to his mind, retained the transcendent spiritual mindset, the contemplative and meditative qualities of the Aryan culture, but not the conquering drive and energy that had driven them into India in the first place. (Just an aside here, about the archaeology: while evidence is limited, it does suggest that the Vedic people may very well have originated in the central European steppe. There is no evidence, however, that they came into India to invade it. There’s an episode of the Tides of History podcast that will take you through all that archaeology in more detail—you can find a link in the transcript on our website, booksofalltime.co.uk.)

Back to Müller: he theorized that the Aryan drive to conquer was the inheritance of the northern descendants of the Indo-Europeans. Thus, in the opinion of Müller and many of his fellow Indologists, it was only right that northern Europeans should now take management of India in hand. Part of this management included explaining Indian literature to Indians. As another German scholar of the time put it, a “conscientious European interpreter may understand the Veda far better,” than any Hindu or other Indian. (Tull 37)

To give him very partial credit, Müller was repulsed when he realized that the leading lights of the emerging “race science” movement began to describe the Aryans as blonde, blue-eyed super-men. Arthur de Gobineau was one of the first to inject this poison into the scholarly mainstream, with his 1855 Essay on the Inequality of Human Races. He used philology, physiology, and the study of history to categorize people into “superior” and “inferior” races. To Gobineau, race was the driving force behind all human history, and it was key that the purest members of the Aryan race—the Germanic and Nordic peoples—should prevail.

This essay validated the prejudices of a great many 19th-century readers—particularly the antisemitism, which is always circulating somewhere in Europe like a virus, ready to latch onto a host and wreak havoc. The essay was used as a pretext to justify colonization and discriminatory legal codes pretty much anywhere Europeans were busy planting flags. (Don’t get me wrong—Americans were also influenced by Gobineau, citing his work when defending chattel slavery, or the Jim Crow laws that followed abolition.)

Perhaps the most enthusiastic disciple of Gobineau was Houston Stewart Chamberlain, a weird mirror-image of Max Müller—an Englishman who went to Germany, where he began his own research into Aryan culture, expanding and simplifying Gobineau’s racism into something more slogan-friendly. Chamberlain spent a lot of time talking through his thoughts about the Aryan race with Kaiser Wilhelm II, until Wilhelm went into exile after World War I. In the 1920s, toward the end of his life, Chamberlain would have numerous meetings with Adolf Hitler.

Given all this, you can perhaps see why people in India tend to be a little on edge when Western scholars start talking about their culture. But for the last few decades, there’s also been something else at work. Something else driving opposition to Western examinations of Indian literature.

Now on to Professor Wendy Doniger. In addition to producing translations of Sanskrit literature, Professor Doniger writes history. Her 2009 book The Hindus: An Alternative History was an attempt to break with the narrow, 19th-century “scriptural” approach to understanding religion preferred by Max Müller and many of his descendants—an approach that came directly from their Protestant Christian view of religion, in which belief stems from diligent study of sacred writing.

In The Hindus, Doniger tried to illustrate how Hinduism has been practiced by ordinary people over the centuries. I’m only about 40% of the way through it at the moment, but I appreciate how it balances an examination of the Vedas and other Hindu literature, which were written by a priestly elite, with evidence about how women and other groups, including the Dalits or “untouchables”, contribute to how Hinduism developed and is practiced (Biswas 2014).

It was initially well-reviewed—it won various prizes in the West and in India, and was praised for its careful research. Then, in 2011, Hindu nationalists discovered it. A pressure group called Shiksha Bachao Andolan, a name that translates to the Save Education Group, filed a lawsuit to have it banned. Under Indian law, it can be a criminal offense, not just a civil one, to publish any media that offends someone’s religion.

In their complaint, the Save Education Group claimed that Doniger’s book made numerous obscene and offensive statements about Hinduism. An extract quoted in a New Yorker article from the time gives a flavor of the accusations: “[The Hindus] is a shallow, distorted, and non-serious presentation of Hinduism … written with a Christian Missionary Zeal and hidden agenda to denigrate Hindus and show their religion in a poor light … The intent is clearly to ridicule, humiliate, and defame the Hindus and denigrate the Hindu traditions.” (Shainin 2014) Weirdly, the lawsuit also concedes that some of the passages in the book it considered offensive—such a 19th-century Hindu monk advising Hindus to eat beef—were very well-sourced.

This lawsuit dragged on until 2014, ultimately resulting in an out-of-court settlement in which Penguin India agreed to withdraw Doniger’s book and pulp all the remaining copies of it within India. There was shock that this relatively small nationalist group could cow a major publisher, and many commentators within India saw this controversy as a major blow against freedom of speech. (NDTV.com 2014)

Doniger defended herself in the NY Review of Books not long after the court case was settled. Her article reveals that the chief complainant against her book has also brought many, many lawsuits against other books by both Western and Indian writers. The Save Education Movement has also put pressure on authorities within India to rewrite history textbooks for primary and secondary students—a crusade that’s been going on for decades.

For example, I found a 2002 article reporting that “[E]ven to mention—let alone to discuss or explore— beef eating in ancient India, the destruction of Buddhist stupas and Jain temples, or the role of a Sikh guru—is denounced . . . the same applies to other delicate topics as the fate of the Indus Valley civilization, the antecedents of the Aryans . . . and the caste system. The range of taboos is very wide.” (Hasan 83)

Doniger mainly lays blame for the whole contretemps on a badly written law, but she also points out that “the misunderstanding arises in part from the fact that there is, in India, no real equivalent of the academic discipline of religious studies . . . [S]tudents in India can study religion . . . in private theological schools of one sort or another, but not as an academic subject in a university. And so the shared assumptions underlying this discipline are largely unknown in India.”

I have no way of knowing if her statement is true or not, so I can’t agree or disagree with that view of the education system. I do agree with what she said later in her essay:

“This argument has nothing to do with religious civility; it is about the clash between pious and academic ways of talking about religion and about who gets to speak for or interpret religious traditions. . . . [we] are talking past one another, playing two different games with the textual evidence. But he thinks there is only one game, and is determined to keep me off my own field. To debate a book you disagree with is what scholarship is about. To ban or burn a book you regard as blasphemous is what fascist bigotry is about.” (Doniger 2014)

This whole situation—lawsuits, religious pressure groups objecting to well-researched history, institutions that should know better suddenly misplacing their spines—sounds depressingly familiar to me. In America, we have our own reactionary pressure groups, motivated at least nominally by religion, who seek to influence the content of textbooks – in 2015, for example, there was a controversy about a history textbook used in Texas that referred to enslaved people as “workers”. I wouldn’t want anyone to give in to those people; I’m sad that Doniger’s publishers gave in to these people.

At any rate, although Doniger’s book was withdrawn from shelves in India and then pulped, there was a bright side. In a 2014 interview with The Hindu, one of India’s newspapers of record, she said that “The flak about that book made it much more popular; thousands of people who had never heard of the book got hold of a copy and read it.” (Nadadhur 2014)

And ten years on, there are signs that Indian voters—the vast majority of whom are Hindus—are not so keen to entertain Hindu nationalist political projects. As I’m recording this, on June 4, India is tallying the votes in its most recent national election—the largest in the world, with 640 million votes cast. It looks like the Hindu nationalist-aligned BJP, the party that has controlled India’s parliament for a decade, has failed to win an outright majority and will need to form a coalition government. It doesn’t put them out of power, but it potentially gives other groups more of a voice.

Anyway, what’s the point of all this? Remember Gregory Rabassa? “Translator, traitor?” He said that one of the major betrayals a translator commits is to present his work as if it’s “the same” as what the author intended. But how can it be? “Can we ever feel what the author felt as he wrote the words we are transforming?” Rabassa asked. (Rabassa 6)

Obviously, we can’t—or at least not for more than a moment or two at a time. To what extent can we ever feel what someone else is feeling? To what extent can we even explain what we are feeling? Ultimately we’re all mysteries to one another—as the protagonist of my favorite movie says: “Nobody knows anybody; not that well.” It seems the answer to this problem of translation is just to accept that it’s a problem. To use my head and thrive upon riddle and enigma, as Professor Doniger suggests in the text I quoted at the top of the show.

The limits of translation—and the limits of literature—are tied up with a capacity for empathy. With the best will in the world, I can only extend mine so far. I’m going to lose nuance reading words across centuries. I’m going to project my own experiences and biases onto whatever I read. I’m never going to be able to consider every viewpoint. But it’s worth carrying on, because I can still glean something from these books—something that takes me outside myself, something that makes me pay attention to the world in a different, deeper way.

I also think it’s worth carrying on sharing what I’m getting from these stories with you. I’ve already heard from listeners who have gone on to read The Epic of Gilgamesh, or Toby Wilkinson’s history of Egyptology, A World Beneath The Sands. It’s really wonderful to hear how those books are making you feel—how they translate, I suppose, for you. And I’d love to hear more.

That’s it for this episode. Thanks for following me down this particular rabbit hole.

What’s next, you ask? Well. Do you like wine-dark seas? Do you like mighty warriors sulking in their tents? Do you like great big lists of ships? You’re in luck: it’s time for the big one, gang. It’s time for Homer’s Iliad, the epic ancient Greek poem of the Trojan War. Join me on Thursday, June 20 for Episode Nine, “The Iliad, Part One – We Wretched Mortals.”

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. The Disclaimer Voice of Doom is Ed Brown. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

Biswas, Soutik. “India Election 2024: Why Modi Failed to Win Outright Majority.” BBC News, BBC, 4 June 2024, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c977g8gl5q2o. Accessed 04 June 2024.

Biswas, Soutik. “Why Did Penguin Recall a Book on Hindus?” BBC News, BBC, 12 Feb. 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-26148875. Accessed 30 May 2024.

Doniger, Wendy. “India: Censorship by the Batra Brigade: Wendy Doniger.” The New York Review of Books, 24 July 2020, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/05/08/india-censorship-batra-brigade/. Accessed 30 May 2024.

Doniger, Wendy. The Rig Veda: An Anthology: One Hundred and Eight Hymns Selected, Translated and Annotated by Wendy Doniger. Penguin, 2005.

Girardot, N. J. “Max Muller’s ‘Sacred Books’ and the Nineteenth-Century Production of the Comparative Science of Religions.” History of Religions, vol. 41, no. 3, Feb. 2002, pp. 213–250, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3176533.

Hasan, Mushirul. “Textbooks and Imagined History: The BJP’s Intellectual Agenda.” India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 1, 2002, pp. 75–90, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23005798.

Hond, Paul. “The Peculiar Perils of Literary Translation.” Columbia Magazine, Winter 2021, magazine.columbia.edu/article/peculiar-perils-literary-translation. Accessed 26 May 2024.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. “Our Master’s Voice: F. Max Müller after a Hundred Years of Solitude.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 15, no. 4, 2003, pp. 305–328, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23551279.

Müller, Max. India: What Can It Teach Us? Books on Demand, 2018.

Nadadhur, Srivathsan. “Wendy Doniger’s Rise after the Ban.” The Hindu, 31 Oct. 2015, http://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/wendy-donigers-rise-after-the-ban/article7823121.ece. Accessed 30 May 2024.

“Penguin to Destroy Copies of ‘the Hindus’: Deeply Troubled by What It Foretells for Free Speech in India, Says Wendy Doniger.” NDTV.Com, 11 Feb. 2014, http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/penguin-to-destroy-copies-of-the-hindus-deeply-troubled-by-what-it-foretells-for-free-speech-in-indi-550543. Accessed 30 May 2024.

Rabassa, Gregory. If This Be Treason: Translation and Its Dyscontents: A Memoir. New Directions Book, 2005.

Shainin, Jonathan. “Why Free Speech Loses in India.” The New Yorker, 13 Feb. 2014, http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-free-speech-loses-in-india. Accessed 30 May 2024.

Tull, Herman W. “F. Max Müller and A. B. Keith: ‘Twaddle’, the ‘Stupid’ Myth, and the Disease of Indology.” Numen, vol. 38, no. 1, 1991, pp. 27–58, doi:10.2307/3270003.

Visweswaran, Kamala, et al. “The Hindutva View of History: Rewriting Textbooks in India and the United States.” Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, vol. 10, no. 1, 2009, pp. 101–112, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43134195.

Wyman, Patrick. “The Rigveda and the Dawn of the Iron Age in South Asia.” Tides of History, season 5, episode 63, Wondery, 22 Feb. 2024. https://wondery.com/shows/tides-of-history/episode/5629-the-rigveda-and-the-dawn-of-the-iron-age-in-south-asia/

Leave a comment