“Some things that happen stamp themselves on their surroundings like an invisible gramophone record. A few people for some reason act like needles and set the record going. I am a needle.” (Budge, quoted in Ismail 407)

On the 21st of March, 1870, a 12-year-old boy reported for work in the offices of W.H. Smith, the London newsagent and bookseller. This was not unusual—it was, after all, high noon of the Victorian era in Britain, and child labour was still the norm. The boy was unusual, however. His name was Ernest, and he had spent four years in a small London school where he had excelled at languages like Hebrew, Arabic, and the relatively new discipline of Assyrian. Now he was to be trained as a clerk – pronounced clark, here on the island – and he would likely remain one for the rest of his life.

Really, young Ernest was lucky. W.H. Smith was a company in its heyday, having just contracted with the railways for exclusive rights to sell newspapers and books at stations. He would be working in the central offices. He could have wound up pasting labels on bottles in a loud, dangerous factory, like the young Charles Dickens, or – more probably – been taken on as a farmhand down in the west country, where he’d been born in 1857.

His mother was a young kitchen maid named Mary Ann. She was unmarried, and when the time came to fill in her son’s birth certificate, she left the space for the father’s name blank. It is really impossible to overstate how much of a handicap that blank space was for a person in 19th-century Britain. It was more than a hole in his biography. It was a hole in his life – one he would spend a great many years climbing his way out of.

Fatherless, illegitimate Ernest learned his letters in Cornwall, where he’s listed as a pupil at a “dame school” – an unregulated, fee-paying school run out of a local woman’s house. At some point, he migrated to London (as so many millions of the rural poor did in those days), where he was recorded as living with his grandmother and aunt – his mother Mary Ann, it can be inferred, died sometime earlier. It was there he attended his modest school, albeit one equipped with a wonderful library. Because Ernest was a diligent boy, he was permitted to read anything from this library. The only catch was that he had to read it systematically, because the headmaster would question him about how he was spending his time.

Much later, when he was in his sixties, Ernest would write about the formative decision he took in the library. “As I wanted to learn all I could about the wars of the kings of Israel and Judah,” he explained, “and as the idea of being able to read the Books of Samuel and the Books of the Kings in the original attracted me greatly, I determined to learn Hebrew.” (Budge 1920, 5)

Please remember: he was eight years old when he determined to learn Hebrew. He taught it to himself out of the books in the school library, then moved on to Syriac, then Arabic, and then, just before he left for W.H. Smith’s, he discovered an exciting, newly deciphered language: Assyrian. Here was a boy who carried worlds in his head – worlds that rang with the languages of prophets and kings. And now he was going to be a clerk in a bookseller’s warehouse.

Again, Ernest was lucky. Other children his age were dying young in mills or in fields or in slums, taking own private worlds with them. Beginning from his perch in the W.H. Smith offices, Ernest would far exceed the future laid out for him on that March day in 1870 by dint of hard work, good social skills, and the occasional application of a very sharp elbow.

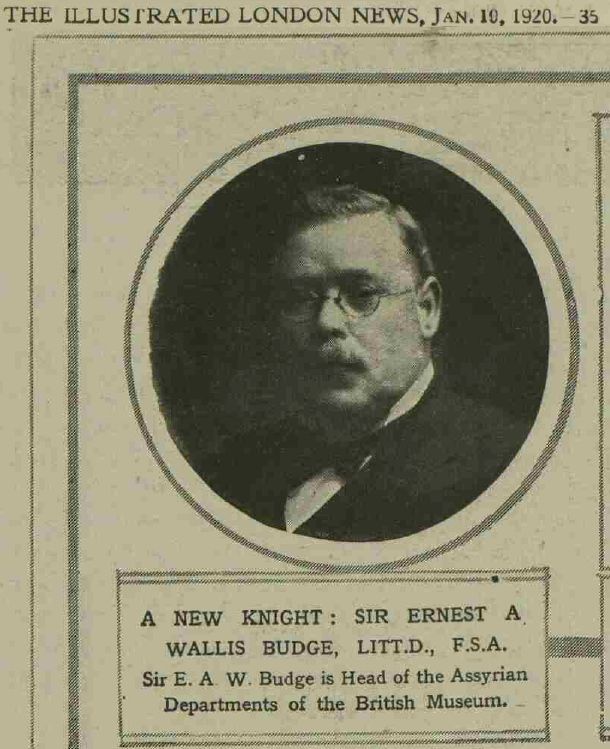

He would become one of the great scholars of his age, a pioneering Egyptologist who travelled all over the middle and near east. He would be an almost insanely prolific author of books and articles on everything from Alexander the Great to Mike, the British Museum’s resident cat. He would also become a sort of tweedy social butterfly, an entertaining raconteur who befriended prime ministers, aristocrats, writers, and the occasional occultist looking for inspiration. In 1920, the same year his memoir was published, he would kneel on a cushioned stool before King George V, be tapped on each shoulder with the flat of a sword, and arise as Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge, knight of the realm.

I’m Rose Judson. Welcome to Books of All Time.

Books of All Time is a podcast that’s tackling classic literature in chronological order. This is episode six: The Egyptian Book of the Dead, Part Two – The Egyptologist and the Magicians. With apologies for the state of my voice – it’s peak tree-pollen season where I am, and all that tree sex makes me hoarse – let’s begin.

So, here we are again with E.A. Wallis Budge. We met him for the first time in episode two, The Library, the Museum, and the Lawsuit, in which he turned up as the villain who’d been found liable for slandering the Iraqi archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam in the 1880s. He made a brief appearance last episode, using his wiles to illegally smuggle antiquities out of Egypt, most notably the Papyrus of Ani, one of the most beautiful and well-preserved examples of the Egyptian Book of the Dead we have.

In this episode, we’re going to get to know him a little better. While I haven’t completely changed my opinion of Budge, I will say that I’ve developed a more nuanced view him. If nothing else, I’m a little in awe of how his research into Egyptian religious and magical practices wound up having a weird afterlife – almost as weird as some of what’s described in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

This episode is very indebted to Budge’s 1920 memoir By Nile and Tigris, but also to Matthew Ismail’s 2011 biography Wallis Budge: Magic and Mummies in London and Cairo. I sometimes think Ismail is a touch too admiring of his subject, but he did do invaluable work digging through archives at the British Museum and the British Library to find correspondence related to Budge that fills in a lot of gaps in his story.

So. How did Budge get out of W.H. Smith’s offices and onto that cushion in Buckingham Palace? As with the story of George Smith, the brilliant printer’s apprentice who went on to decipher the Epic of Gilgamesh, it begins with lunch breaks. Really, where would so many of our social sciences be without Victorian-era lunch breaks?

Budge was determined to keep studying Hebrew, Assyrian and other Eastern languages, even if he couldn’t go to school anymore. However, he was too young to be admitted into the British Museum’s reading room by himself when he first started his job (George Smith, you may recall, was in his early 20s when he started his career). Instead, Budge began by sourcing what books he could from W.H. Smith stock, and then did his studying in the library at St. Paul’s Cathedral, writing occasionally to the former Hebrew tutor at his school for guidance about what to read next. This tutor was a scholar called Charles Seager, who had been a professor at Oxford until he converted to Catholicism – a firing offense in those days. Seager was the first in a long chain of benefactors Budge would encounter throughout his life. These benefactors were usually older, and usually male. There’s an obvious – and almost certainly oversimplified – conclusion to be drawn about that. Ismail sums it up this way:

“Budge always respected strong, practical, successful and paternal men who were not only helpful to him, but who were also willing to give him the sort of advice and support he might have hoped for from a father.” (Ismail 9)

In other words, Budge would always be looking to fill that blank space on his birth certificate in some way.

Back to Dr. Seager: in addition to guiding the boy’s continuing study of Hebrew, Syriac, and Assyrian, Seager was also a close friend of Samuel Birch, who happened to be the Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum and the president of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. Birch, who had collaborated with Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam, as well as directing the work of George Smith – names that will be familiar to anyone who listened to our episodes on The Epic of Gilgamesh – “was, for forty years, the most important Egyptologist in England, sought out by scholars and dealers in antiquities from all over Europe.” (Ismail 10)

In 1872, after George Smith presented his paper on the Gilgamesh flood story to the Society of Biblical Archaeology, Dr. Seager brought 15-year-old Budge to the Museum to meet Birch, informing him that the boy had made some progress learning to decipher cuneiform tablets. Birch, whose working-class wunderkind George Smith had just made a splash, seemed willing to take a chance on another bright boy with an obscure past. While he couldn’t make an exception for Budge in the matter of the British Museum reading room – the boy was still too young – Birch did agree to let Budge come to his office now and then to look at more books on Assyrian subjects. It was an opportunity Budge seized.

You must remember: this boy was working five and a half days a week, probably ten hours per day. While it’s true there were fewer distractions for people in those days – no television, no professional sports, certainly no YouTube unboxing videos to watch – this continued persistence at his studies demonstrates a positively heroic work ethic that one has to respect.

His regular visits to Birch’s offices to study inevitably led to even more fruitful meetings. Budge became acquainted with George Smith and Sir Henry Rawlinson, who encouraged and even guided his study of Assyrian. He was loaned books he could not afford, and eventually allowed to work with actual cuneiform tablets. When a group of orientalist scholars began to offer lectures to young working men on Assyrian and the Egyptian hieroglyphics, Budge was allowed to attend them, deepening his understanding of cuneiform and pursuing a new avenue of study in Egyptian. He would also attend meetings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology in the company of Charles Seager – meetings which were sometimes held at the home of William Ewart Gladstone, the former Liberal Prime Minister. The Boy Budge was being drawn into the orbit of some very bright stars indeed.

While these connections at the Museum were flourishing, Budge continued to study at St. Paul’s Cathedral when he could, and here his remarkable diligence attracted another supporter: John Stainer, the Organist of St. Paul’s. Stainer’s role at St. Paul’s wasn’t just about performing during services. Educated at Oxford, he was also the director of music for the great cathedral and an author of numerous books about music. When, in 1877, the British Museum had a vacancy for assistantship – an entry-level position, essentially – Stainer saw the opportunity to help Budge further. He wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury praising Budge, and asking for the Archbishop’s support for the young man’s application (Budge was by then almost 20). It was part of the requirements for the post that one of the Trustees of the British Museum should write a testimonial supporting the applicant. The Archbishop was one of these.

“It is evident,” wrote Stainer to the Archbishop, “that a young man of such talent ought not to be with a pen behind his can in a book shop . . . . I believe the smallest hint from His Grace would secure a post for this orphan.” (Ismail 20) Budge’s Hebrew tutor Charles Seager also wrote a testimonial on his behalf, underscoring the point that the only thing holding the young man back was the need to work full time: “I regard him as an industrious, intelligent and altogether (supposing him to have the time necessary) a well-promising student.” (Ismail 21)

While his friends badgered the Archbishop, Budge decided to write to two other trustees and ask for their support: one was the founder of the company for which Budge worked, William Henry Smith. The other was William Gladstone. W.H. Smith could not help him, but was impressed. Gladstone did help him, and when the post wound up going to another young man anyway, he continued to be interested in Budge’s fortunes. It was suggested that Budge might want to be sent out to the British Museum’s digs in Mesopotamia, to help Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam, neither of whom knew how to read cuneiform (Ismail 24), but this did not come to pass – it’s interesting to ponder whether the later conflict between Budge and Rassam would have been avoided if it had.

“It would be a discredit to the country to allow such a simple-minded genius to be crushed by cold neglect,” wrote Stainer to Gladstone. It was eventually decided that Budge should go to Cambridge University. His rudimentary primary education was a concern – he had little command of mathematics, Latin, or Greek – but Cambridge had just created a new degree in Semitic languages which seemed tailor-made for the young man. The goal of his benefactors was to groom him for a career in academic research, or, failing that, for curatorial roles at the British Museum. Budge’s benefactors clubbed together to pay his fees and living expenses, and he was off.

Budge spent the next three years studying for the Semitic languages Tripos – and, if you’re wondering, “tripos” is just Cambridge’s weird way of naming its final exam for bachelor’s degree students. It originates from a now-defunct tradition in which students had to obtain their degree in part by arguing with a graduate student seated on a three-legged stool. That is, a tripod, or tripos. Now you know.

Budge applied his usual diligence to his studies at Cambridge, but in spite of winning a scholarship for his Assyrian work, he was constantly tripped up by the threadbare nature of his earlier education. He didn’t have enormous swathes of Homer committed to memory. He had not spent as much time as the other young men sweating over Euclidean geometry, or fighting his way through passages of Cicero. Budge’s writing (ironically, considering he would go on to publish dozens of books and papers) was judged as lacking style and clarity. But he was very knowledgeable in his chosen languages, and he also picked up the study of Coptic at Cambridge, on the principle that it might help him to eventually study ancient Egyptian – Coptic, you’ll recall from episode four, had been key to Jean-Francois Champollion’s breakthrough with hieroglyphics.

When it came time to sit the tripos he only managed a second-class degree. This was disappointing to his benefactors, but it was still enough to get him officially employed by the museum at last. He would remain there for the next 41 years of his life, spending 30 years as the Keeper of the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities. I’ve already given a glimpse of his career there in previous episodes: his being found liable for slandering Hormuzd Rassam; his very chancy visits to Egypt and other parts of the Middle East on “acquisition” visits for the museum that often involved unethical smuggling or outright flouting of laws.

Ismail tries to excuse these aspects of Budge’s career to a certain extent. I’m more or less on board with one of his ideas – namely, that Budge’s methods for acquiring new artefacts for the museum, in addition to being an inevitable outgrowth of the paternalistic, colonial mindset of many British people during the Victorian era, were approved of, and in some cases even recommended by, his employers. He was just doing his job, mate. It doesn’t make it right, even within the context of the time, but it does make it understandable.

I’m less on board with the idea that the unfounded accusation Budge made against Hormuzd Rassam – claiming that Rassam had been orchestrating the theft of artefacts from British Museum excavation sites, rather than merely unable to stop them – are excusable due to bad information Budge had received, or that they were due to Budge’s feelings of social and financial insecurity early on in his career. His slanderous accusation may be somewhat explainable due to these factors, but not excusable – not even if Rassam was, as Ismail’s presentation of the evidence demonstrates, spread very thin and possibly even not as diligent in ensuring the security of the many sites he was charged with supervising – often without pay – across Iraq. Budge lost the court case, and should probably have lost his job, too.

But he didn’t, and while we can’t go into every detail of a four-decade career here, we can go into the influence his scholarship on Egypt would have on another circle of prominent people swirling around the British Museum at this time – occultists and esoteric thinkers.

As serious and scholarly as he was, Budge, like many Victorian academics, was not entirely opposed to the idea that psychic or paranormal phenomena were real. Budge claimed that both his mother and his grandmother, for example, were given to dreams about the future, (Ismail 35) and that he himself occasionally experienced them – that text I quoted at the top of the episode, about the gramophone needle? That’s Budge talking about himself. He described one of his precognitive dreams to his friend, the author H. Rider Haggard. The dream occurred while Budge was at Cambridge. It was the night before an important exam in Assyrian and Akkadian, and:

“Budge dreamed a dream in which he saw himself seated in a room that he had never seen before – a room rather like a shed with a skylight in it. The tutor came in with a long envelope in his hand, and took from it a batch of green papers, and gave one of these to Budge for him to work at . . . the tutor locked him in and left him.” (Haggard, quoted in Ismail 34)

In the dream, Budge looked down at the green exam paper and he saw that it contained four Assyrian texts he couldn’t translate, and he became so overwhelmed by anxiety that he woke up and went down to his study. Flipping through his books to calm himself down, realized that he had found the texts in one of Henry Rawlinson’s books. He set about translating them until the sun came up, figuring to get some last-minute practice in if nothing else, and then went off to do his exam.

When he arrived at the hall where examinations were held, it was full, and the tutor led him off into – you guessed it – a shed-like room with a skylight. The events of the dream, according to Budge, repeated themselves: the green exam papers, the tutor locking him in, and the very same texts he had dreamed about that night. He aced the exam.

Budge was also interested in ghosts, associating with the London Ghost Club, but never actually joining. He occasionally invited mediums and others to visit him in his offices, and he gifted people amulets with apparently sincere belief in their powers.

“It is obvious that Budge was not only interested in the occult himself, but his works on Egyptology were also a very important source of information for many . . . people who were engaged either in escaping or reforming their relation to the Christian past or constructing their pagan present.” (Ismail 406)

The turn of the 20th century was a boom time for alternative spiritualities. The literalist understanding of the Christian bible was being eroded – though not specifically denied – by Darwin’s publication of the theory of evolution, and by many of the discoveries scholars like Budge were making about the history of the Biblical era. In some quarters, there was a hunger for something “truer” than the Bible, but not as dry and academic as science or history.

Various forms of mysticism attempted to thread this needle, patching together bits of renaissance-era Christian occultism, such as Rosicrucianism, Modern Spiritualism, which had brought its seances around tables over from America, and various Masonic-inspired groups who looked, in part, to new discoveries about Ancient Egypt for guidance in developing supernatural or psychic powers.

The Irish scholar Kathleen Raine, in her short 1976 book Yeats, the Tarot, and the Golden Dawn, notes that while ideas about Ancient Egypt as a nation of magicians had been circulating since the ancient Greeks, the post-Champollion explosion of scholarship offered esoteric thinkers and mystics new possibilities to play with. “Egyptian mythology had the double charm of antiquity and novelty,” she wrote. “It was all new: the pantheon of the land of magic; Thoth, Isis, Osiris, Horus, Hathor and Maat had not become, like Venus and Cupid and Apollo, a currency worn thin by use.” (Raine 7)

While there were many esoteric groups circulating in the English-speaking world that looked to Ancient Egypt as the origin of magical practice – a school of thought known as Egyptosophy – possibly no organization took Budge’s scholarship and ran with it more than the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

The Golden Dawn was founded in 1888 – coincidentally, the same year that Budge acquired the Papyrus of Ani for the British Museum. Its three founders synthesized different strands of Christian and Jewish mysticism – Rosicrucianism, Kabbalah – and also pulled together various ideas from Freemasonry, which had begun as a strictly Christian organization, but was, by the late 1800s, morphing into something a little more occult. Additional ideas about Ancient Egypt, particularly when it came to dressing for group rituals, added additional spice to the Golden Dawn stew.

Because they were based in London, the members of the Golden Dawn made many trips to the British Library and the British Museum for research into the various wisdom traditions they were busily co-opting – in fact, Samuel Mathers, one of the order’s co-founders, picked up a woman named Mina Bergson in the museum as she was sketching one of the Egyptian statues on display (Greer 55). The high period of the order’s operation coincided with Budge’s tenure as Keeper at the Museum. We know that Budge was personally acquainted with two prominent members of the Order, (Magus 77) and that his work heavily influenced a third member. This overlapping of Budge’s social circles would later lead to some spicy rumors about him.

First, word got around that he was an initiate of the Golden Dawn himself, and second, that he ran his own chapter from within the British Museum, allowing the use of genuine Egyptian antiquities in rituals. (Magus 77-78) Unfortunately, there’s no real evidence for either of these stories, though I do love the idea of him dressing up in a Thoth mask and reciting spells (a thing the Golden Dawn members did) or flipping over tarot cards (another thing they did) or attempting to get into a trance and astrally project himself somewhere. Budge, if you’ve not seen a photo of him – there’s one with the transcript of this episode at our website, booksofalltime.co.uk, was a round, owlish-looking little man, and if his astral projection wound up in my room at some point I would probably be more annoyed than impressed.

The works of Budge that mattered most to the occultists were his 1896 translation of The Egyptian Book of the Dead and his 1899 book Egyptian Magic. Having tried to read both these works, I really cannot imagine how they were inspiring to anyone. In these books, Budge’s style is completely stripped of the charm and verve that’s so often present in his memoir – I’ve quite literally read myself to sleep with Egyptian Magic. Here’s a flavor of it:

“Now Khufu had for a long time past sought out the aptet of the sanctuary of Thoth, because he was anxious to make one similar for his own ‘horizon’. Though at the present it is impossible to say what the aptet was, it is quite clear that it was an object or instrument used in connection with the working of magic of some sort, and it is clear that the king was as much interested in the pursuit as his subjects.” (Budge 1899, 12)

It’s not quite stereo instructions, but it’s not far off. Back to the Golden Dawn. In the 1880s, Budge joined the literary Savile Club, which brought him into contact with writers like Rudyard Kipling and H.G. Wells, and also with the Irish poet (and future Nobel laureate) William Butler Yeats, who was one of the original members of the Order of the Golden Dawn. Yeats is probably best remembered today for his dark, brooding poem The Second Coming(1919), which references the sphinx and closes with the haunting question, “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last/ Slouches toward Bethlehem waiting to be born?”

Yeats was deeply invested in the Order from its founding until his resignation in 1905. Kathleen Raines quotes him as recalling his time there wistfully later on in his life, writing:

“We all, so far as I can remember, differed from ordinary students of philosophy or religion through our belief that truth cannot be discovered, but may be revealed . . . [the Order] recalled certain forgotten methods, chiefly how to so suspend the will that the mind became automatic, and a possible vehicle for spiritual beings.” (Raine 11)

For Yeats, spiritual pursuits were very much about tapping into a channel that would keep the garden of his poetic inspiration well-watered. Letters he wrote to his fellow Golden Dawn members show that he certainly read Egyptian Magic, and that he took a keen interest in Budge’s explanation of the power of words to the Egyptians. As you would do, if you were a poet.

The second member of the Order of the Golden Dawn who is known to have met Budge on several occasions was the woman who eventually became a leader of the group: Florence Farr. Farr was a beauty, and had a glittering career as a popular West End actress. She was a muse of Yeats’s, and also the muse and romantic partner of another great man who was briefly involved with the Order – the playwright George Bernard Shaw, who created roles for her in plays like Arms and the Man (1894). But she eventually left the theatre, preferring to rise up the ranks of the Order and pursue her other interests – namely, the study of ancient Egyptian religion and the pursuit of women’s rights.

When Farr left the stage, Shaw was furious. In the book Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses, Mary Greer quotes an acid letter from Shaw to Farr: “Now you think to undo the work of all those years by a phrase and a shilling’s work of esoteric Egyptology.” (Greer 176) That is exactly what Farr did think – she spent huge swathes of time in the British Museum’s reading room, researching Egyptian religious practices, or, according to Caroline Tully of the University of Melbourne, communing with the spirit of a mummy on display in the museum. (Tully 13)

Farr sought the advice of Budge and other Egyptologists when she needed resources, and in addition to incorporating Egyptian themes into her magical work, she also produced several books and articles on the subject – though it should be noted that these are heavily slanted by her mystic and esoteric interests. In a different age, she would probably have had access to a proper education, and become a popular communicator of Egyptian history – I imagine her as a sort of witchy, Stevie Nicks-ish version of Professor Mary Beard, a classicist who, among other things, presents numerous documentaries about the Romans over here in the UK.

There is no evidence that the Great Beast, Aleister Crowley, ever met E.A. Wallis Budge, but he certainly read Egyptian Magic, and like so many other things – sex, hallucinogens, booze – it went completely to his head. Crowley came late to the Order of the Golden Dawn, and he didn’t stay long, because he wasn’t very popular at all. By 1900, the Golden Dawn had split into two factions – one headed by Florence Farr in London, and another by Samuel Mathers in Paris.

Crowley was a henchman of Mathers’s, and in April 1900 he was sent to London to try to take control of the original Golden Dawn temple through magic. Specifically Celtic magic. He turned up dressed in a kilt with a dagger, shouting curses. He was confronted by Yeats and another member of the order, and the whole affair ended with Yeats booting Crowley down the stairs. There is a very hilarious and well-researched recounting of this donnybrook, which came to be called “The Battle of Blythe Road” on the “Odd This Day” blog, kept by a fellow who goes by the name of Coates. It’s worth a read, and I’ve linked it with the reading list, which you can find at the bottom of the transcript of this episode. There’s a link to the transcript in the show notes.

Crowley was also obsessed with ancient Egypt. Caroline Tully provides a careful retelling of his trip there in 1903 in a 2010 article. She describes how Crowley was done with the Order by this point, and also newly married to a woman as daft as himself. He and his wife Rose (no relation) went to Cairo for their honeymoon, where they communed with artefacts in the museum, conducted unspecified (and probably sexual) rituals, and eventually claimed that Crowley had received a revelation that a new ‘Aeon of Horus’ had begun, and it was his duty, obviously, to translate the wisdom of Horus to the masses. Or something. Tully sums it up this way: “After Crowley’s experience with the Golden Dawn he sought to create a new magical tradition, but looked backward to the ancient Egyptian past for validation.” It was an ancient Egyptian past the Order had half-imagined, and half-learned from Budge and his colleagues.

Finally, the one person Budge may have had the most influence on with his scholarship wasn’t a member of the Order at all. He was a writer, insanely famous in his time, but more of a curiosity today. H. Rider Haggard was the author of more than 50 books – rollicking adventure-type stories set in the quote-unquote exotic eastern reaches of the British Empire.

Haggard lived a life on the periphery of adventure – he’d been a minor colonial bureaucrat in South Africa, mixing with explorers and military men – before moving back to London in the 1880s. He became a close friend of Budge’s – according to the author Simon Magus, Haggard nominated Budge to the Savile Club, and it’s from Haggard that we have the story about the precognitive dream Budge had before his exam at Cambridge. (Magus 77) As Haggard began his writing career, he drew on Budge’s knowledge of Egyptian and Middle Eastern religions to give color to his stories.

His most famous novel, King Solomon’s Mines, featured a hero called Allan Quartermain whose exploits would inspire generations of storytellers and filmmakers including George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Quartermain is a direct ancestor of Indiana Jones, and the vibe of Haggard’s writing also informs 1999’s The Mummy – two films which have shaped popular imaginings of Egypt and archaeology – imaginings that, if you squint, are marked with the busy fingerprints of E.A. Wallis Budge.

Well, you weren’t expecting that, were you? I admit that I didn’t anticipate developing quite so much sympathy for the devil Budge when I set out to research this episode. Still, while he’s more impressive than I initially thought, I can’t help but feel ambivalent about him.

Budge died in 1934 – he had married, but never had children – and his legacy at both the British Museum and in Egyptology have been called increasingly into question over the last 90 years. The study of ancient Egypt (and archaeological practice generally) has advanced far beyond him,. His sharp dealings with Hormuzd Rassam, as well as his complicity in the looting of imperial territories (however socially sanctioned in his time) mean that he’s also justifiably seen as embarrassing, if not shameful. And I suppose I’ve contributed to that, seeing as how so many of you have messaged me or posted on Instagram about how much you hate the guy after hearing about him on this show.

I guess what I’ve learned so far with this project is that everything we know about ancient literature and ancient cultures is interpreted for us by a whole lot of Budges. There’s no pure experience of Assyrian or Egyptian literature for the likes of us, and probably not even for people who can read cuneiform or hieroglyphs. And there are no pure interpreters – there are just people bogged down in their own times and politics and personalities, trying now and then to find connections to events and stories that let them glimpse beyond the boundaries of an all-too-short life.

We’re leaving Egypt behind now, along with the infighting of 19th century archaeologists. Our next episode heads to India, where we’ll be engaging with a selection of the beautiful hymns and myths of the Rig Veda, the oldest versions of which stretch back to about 1500 BCE, and parts of which are still used in Hindu religious practices today. That’s The Rig Veda, Part 1: Breathed by Its Own Nature, coming on Thursday, May 23.

Books of All Time is written and produced by me, Rose Judson. Lluvia Arras designed our cover art and logo. Special thanks to Yelena Shapiro, Cathy Merli, Matt Brough and the Books of All Time Advisory Council: Ed Brown, Beck Collins, Neil Dowling, Caitlin McMullin, Hugh Parker, and Jonathan Skipp. You can support the show by subscribing and leaving a rating or review at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. Thanks for listening! I’ll be back in two weeks.

References and Works Cited:

Budge, E.A. Wallis. By Nile and Tigris. John Murray, 1920.

Budge, E.A. Wallis. Egyptian Magic. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1899.

Coates. “Odd This Day: 19 April.” Medium, 19 Apr. 2023, mulberryhall.medium.com/odd-this-day-eb0ab552f3b3. Accessed 08 May 2024.

Greer, Mary K. Women of the Golden Dawn: Rebels and Priestesses. Park Street Press, 1996.

Ismail, Matthew. Wallis Budge: Magic and Mummies in London and Cairo. Dost Publishing, 2021.

“Magic, Alchemy, and Hermeticism.” Magic, Alchemy, and Hermeticism | Echoes of Egypt, Yale University Peabody Museum, echoesofegypt.peabody.yale.edu/egyptosophy/narrative. Accessed 08 May 2024.

Magus, Simon. Rider Haggard and the Imperial Occult: Hermetic Discourse and Romantic Contiguity. Brill, 2022.

Melton, J. Gordon. “Spiritualism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 22 Mar. 2024, www.britannica.com/topic/spiritualism-religion. Accessed 08 May 2024.

Raine, Kathleen. Yeats, the Tarot and the Golden Dawn. Dolmen Press, 1976, available at: https://archive.org/details/yeatstarotgolden0000rain/page/10/mode/2up?q=egypt

Tully, C. J. 2010. Walk Like an Egyptian: Egypt as Authority in Aleister Crowley’s Reception of The Book of the Law. The Pomegranate: International Journal of Pagan Studies 12:1. 2010. 20–47.

Leave a comment